Dio or Don’t You?

Another short interlude while I get some more ducks in a row...

Dio or Don’t You?

One of the things about research is that in pursuing any path of inquiry, the chances are pretty high we’re walking in the footsteps of someone else, especially if you’re a relative newcomer to the discipline, as I am. So at least in my case, when this happens, it provides some confidence I’m not wandering about entirely aimlessly, which is a comfort even if it, in a sense, steals my thunder. This happened in the course of my current pursuits, and since I’m at a crossroads as to which part of my research to present next, I thought it might be amusing to share it while I try to get my ducks more in a row.

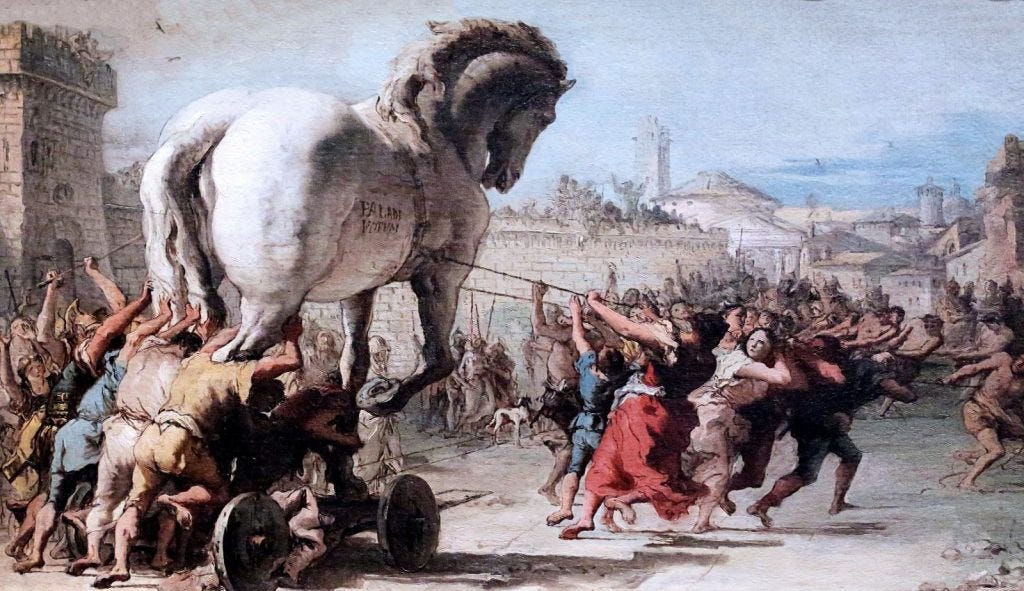

First, a bit of background is in order, as it is part of what motivated me to embark on this whole investigation in the first place. For many years, two aspects of the Trojan War legend rankled: Helen’s elopement with Paris and the Trojan Horse. As parts of a myth and a cracking good story, they could be accepted, but as things that could happen in reality, they took on a taint of absurdity. More puzzling to me, the Iliad does not mention either of them.

Yet, even as it became more and more apparent there was a historical reality behind the Trojan War legend, serious historians (including my personal favorite, Barry Strauss) seemed to entertain these events as real possibilities (I hastened to add Strauss does not embrace the horse myth, the one I find more egregious), but without addressing how realistically they could be pulled off.

Setting aside the wooden horse, I never understood exactly how it was that Helen and Paris could have made off with Menelaus’ treasure. The story handed down to us is that he left town (usually for Crete), Paris seduced Helen, they hooked up (contradicting the Iliad), loaded up the goods and decamped. Proclus’ summary of the Cypria indicates that after their canoodling, Helen and Paris escaped in the middle of the night. How exactly? Did the king’s staff, guards and servitors simply stand around while Helen and a foreign prince cleaned out the treasury? Who provided the transport and helped load it all? Did Paris have a retinue for this? What excuse did they give? Sparta is about 25 to 30 miles from the coast, maybe 8 to 10 hours with a heavily laden cart. They went on their merry way, jolting down the roads with wagon-loads of gold and nobody bothered them?

To the best of my knowledge, no historian has really addressed this. I tried, but couldn’t come up with an explanation that wasn’t a serious violation of Occam's razor. The Occam's razor solution was that Helen married Paris and the wealth transferred was her dowry. This realization helped inspire my research, the fruits of which I’ve been posting here.

So imagine my surprise when my research turned up what I might call a kindred spirit who had not only beaten me to the punch on these specific questions, but anticipated some of the answers I arrived at by roughly 2,000 years. The individual responsible is Dio Chrysostom, a Greek writer, orator, Platonist, stoic, sophist and, for a time, cynic philosopher, of the 1st century AD. He achieved some notoriety in his day – writing on a number of topics, traveling widely and being exiled for criticizing the Emperor Domitian – but he has not fared well in the annals of Homeric scholarship, if indeed he has figured at all. Only one mention did I find in the references I initially consulted and it did little more than state his name; further searches revealed not much more, but they did turn up his “Eleventh Discourse Maintaining that Troy was not Captured.”

Frankly, I am not terribly surprised; Dio appears to be a bit of a crank. His discourse begins:

I am almost certain that while all men are hard to teach, they are easy to deceive. They learn with difficulty – if they do learn anything – from the few that know, but they are deceived only too readily by the many who do not know, and not only by others but by themselves as well. For the truth is bitter and unpleasant to the unthinking, while falsehood is sweet and pleasant.

He then continues:

But though, as I have said, it is hard for men to learn, it is immensely more difficult for them to unlearn and learn over again, especially when they have been listening to falsehood for a long time, and not only they themselves, but their fathers, their grandfathers, and, generally speaking, all former generations have been deceived. For it is no easy matter to disabuse these of their opinion, no matter how clearly you show it to be wrong.

Please bear in mind this is Dio Chrysostom speaking, not me. He goes on to take a fling at Homer:

For when Homer undertook to describe the war between the Achaeans and the Trojans, he did not start at the very beginning, but at haphazard; and this is the regular way with practically all who distort the truth; they entangle the story and make it involved and refuse to tell anything in sequence, thus escaping detection more readily.

Warming to his argument, Dio lays out all the ways Homer intended to deceive his listeners, speaking of those who “lie skillfully” by presenting the facts out of order, how he didn’t tell the beginning and end of the story “in a straightforward way” but when he does make mention of them “it is incidental and brief, and he is evidently trying to confuse,” and accuses Homer of not being “straightforward or frank when telling of the abduction of Helen or the fall of Troy.” Shortly after this barrage, he develops his theme further:

If it was his wish to tell of the death of illustrious men, how is it that he omitted the slaying of Achilles, Memnon, Antilochus, Ajax, and of Paris himself? Why did he not mention the expedition of the Amazons and that battle between Achilles and the Amazon, which is said to have been so splendid and so strange?

At this point, Dio is tracking my thoughts very closely – or more properly, I’m tracking his. But then, either charmingly or absurdly depending on one’s point of view, he claims to reveal the “truth” of what happened, putting it in the mouth of a “certain very aged priest” from Egypt (a nod to – or poke at? – Herodotus?):

I, therefore, shall give the account as I learned it from a certain very aged priest in Onuphis, who often made merry over the Greeks as a people, claiming that they really knew nothing about most things, and using as his chief illustration of this, the fact that they believed that Troy was taken by Agamemnon and that Helen fell in love with Paris while she was living with Menelaus…

After taking a fling at Stesichorus (Dio is ecumenical in his condemnations), his informant embarks on a long retelling of the legend, beginning not with Zeus’ plan to unburden the Earth, but with Tyndareus and his family. After discussing the question of Helen’s impending marriage, Dio’s priest has this to say regarding Helen eloping with Paris:

“Then see,” continued the priest, “how foolish the opposite story is. Can you imagine it possible for anyone to have become enamored of a woman whom he had never seen, and then, that she could have let herself be persuaded to leave husband, fatherland, and all her relatives – and that too, I believe, when she was the mother of a little daughter – and follow a man of another race? It is because this is so improbable that they got up that cock-and-bull story about Aphrodite, which is still more preposterous. And if Paris had any thought of carrying Helen away, why was the thing permitted to happen by his father, who was no fool, but had the reputation of having great intelligence, and by his mother? What likelihood is there that Hector tolerated such a deed at the outset and then afterwards heaped abuse and reproach upon him [Paris] for abducting her as Homer declares he did?

I have to admit, I was rather tickled by the “cock-and-bull story about Aphrodite” part. But here Dio is, raising the same problems that always niggled me. He then asserts that Paris came not as a guest, but a suitor and Tyndareus preferred him as a son-in-law to any of the various Greeks competing for Helen’s hand. He goes on to cite other examples, including the story that the daughter of Cleisthenes, the tyrant of Sicyon, was “wooed by a man from Italy,” Pelops coming from Anatolia to marry Hippodamia, Theseus marrying an Amazon queen and Io coming to “Egypt as a betrothed bride and not as a heifer maddened by the gadfly.”

The point Dio makes here, regardless of the legendary nature of his examples, is that dynastic marriages were a major part of the political fabric of the Bronze Age and the Mycenaeans were not left out. From here on, I’ll leave off quoting Dio. The rest of his discourse makes for fun reading, and I urge anyone interested to read the whole thing. It’s online at LacusCurtius:

Dio Chrysostom. “The Eleventh Discourse – Maintaining that Troy was not Captured.” https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Dio_Chrysostom/Discourses/11*.html

He concludes that Troy was not captured by the Greeks – which I have concluded as well – but came home and cooked up a story to cover their failure – which I don’t agree with – but in advancing that idea, Dio shows us that there is very little new under the sun.

Am I (or should I?) rely on Dio as a source to support my nascent conclusions? No, I’m not (not to any great degree anyway) and I probably shouldn’t. Between his tone, his Egyptian priest and his hyperbole, it’s small wonder he hasn’t been taken seriously. It’s doubtful he had some as-yet-undetected historical sources for his statements and the same arguments can be put forward without recourse to him. In fact, it’s far from clear he took himself seriously. The preamble on LacusCurtius says:

The eleventh Discourse is interesting to us because it contains a great deal of the criticism of Homer from Plato’s time down; and because it seems to be so evidently just a “stunt” to show what could be done to disprove what everyone believed to be a fact, some would assign it to the period before Dio’s exile when he was a sophist… Others feel that in view of the self-assurance of the speaker and the skill with which he presents his arguments, the speech belongs to Dio’s riper years and that he had some serious purpose in delivering it.

Whether Dio indeed had some serious purpose in delivering his discourse or not will have to remain an open question, but I thought that in blazing a trail for me, whether he meant to or not, I ought to give him his just due.