It is acknowledged that Homer’s Iliad has been subjected to editorial revision during its long history, some of which appear to have occurred early on. These revisions are distinct from the questions of multiformity imposed by its predominantly oral dissemination. In this essay, I will examine three of the most significant, and probably earliest, revisions (technically referred to as interpolations) in regards to how they may have changed, and possibly obscured, the original intent of Homer’s Iliad.

Keywords: Homer, the Trojan War, the Iliad, the Sack of Troy, Iliou Persis, the Homeric poems, the Cyclic poems, Odysseus, the Judgement of Paris.

Acknowledgements: I am deeply indebted to Cynthia Gralla of Royal Roads University for her kind assistance and support in the creation of this work, including help with research, excellent editorial suggestions and many insightful comments. Without her encouragement, these essays could not have been written. The insights of Eric Luttrell of Texas A&M, in both his emails to me and his online lectures, were indispensable in helping me better understand my subject. I highly recommend anyone in these topics invest the time to watch them. They are linked at the end of this essay.

Introduction

My title is a nod to – or a riff on – Gregory Nagy’s 2015 article, “Pindar’s Homer is not ‘our’ Homer”; I hope I may be doing so in a good cause. What is that cause? Simply to see what might be done to “recover” the Iliad Homer envisioned as he composed it over a many years, quite possibly amounting to more than a decade. As I’ve discussed previously, Nagy and his compatriots deny that any such “original” Iliad, composed (in writing) by an individual, existed. Rather than recapitulate the reasons I’ve concluded otherwise, for brevity’s sake I’ll limit myself to saying that two things can be true at the same time, and while the hypothesis that Homer wrote the Iliad can explain the evidence the Oralist school puts forwards, I (following Martin West) hold that their hypothesis cannot adequately explain the textual artifacts we see in the Iliad itself (see Homer and the Written Word for my thoughts on this).

Attempting to recover Homer’s Iliad matters because it might point to a Bronze Age tradition of a historical Trojan War, and offer hints as to what that tradition could have been. At this point, I might be accused of putting the cart before the horse since I’ve already put forward my ideas, giving this an air of an ex post facto justification, rather than (as might be more usual) presenting this as a step toward forming those suppositions. I therefore beg the indulgence of my readers in that regard.

Next, I must say that recovering Homer’s Iliad is the subject of Martin West’s 2011 book, and there is no way I can do it anything like true justice. My discussion here, and in future essays, will necessarily be cursory, top-level, and no doubt oversimplified. My hope is to give a flavor of West’s analysis along with some observations of my own that led me toward my notion that Homer composed his epic based on an “epic historical” tradition which existed in parallel with a mythopoetic tradition that evolve to rationalize the Bronze Age collapse and its consequences.

In this essay, I’ll discuss three significant changes evidence indicates were made to the Iliad, possibly around the mid-7th century (see my roadmap) to make it conform to the mythopoetic tradition: Book 10, to set the stage for Odysseus becoming the primary Greek hero after the death of Achilles and by extension, introduce the Trojan Horse; the allusion to the Judgement of Paris in Book 24, and statements about the sack of Troy in Books 12 and 15. All these topics are crucial to the mythopoetic tradition and Trojan War legend as we have it and none may appear in the original Iliad, strongly suggesting (if true) its composition was based on an independent tradition.

I’ll start with Book 10 because it is the least controversial; the general consensus in Homeric scholarship is that it is a later addition. Casey Dué has an interesting take on the roots of Book 10 in an ancient form she terms “the poetics of ambush” but this does not bring into question that Book 10 is an interpolation, merely that the author of Book 10 was inspired by preexisting models that might date from well before Homer. Accordingly, I won’t review the arguments supporting Book 10 being an interpolation, but instead discuss what appear to be the most likely reasons for promoting Odysseus to his new role, as it might strike us (or, at least, me) as an odd choice.

Odysseus

Odysseus is a fascinating character, quite different than the other Greek heroes like Ajax, Diomedes, and especially Achilles; also quite different than Hector. While being a formidable warrior, martial prowess is not his main characteristic.1 Instead, it is his mental capabilities that distinguish him.

The invocation of the muse in the Odyssey describes Odysseus literally as a “man of many turns” (πολύτροπον, polytropon); per Prof. Eric Luttrell), a description I much prefer to calling Odysseus “a man of many devices” or just a “complicated man,” as occurs in other translations. Polytropon can be taken to refer to three things about Odysseus: first, and most simply, to all the “turns” he must make on his way home; not just the fact he gets physically batted here and there, but has to overcome multiple challenges and has different adventures.

Next, it can be taken to refer to his morally ambiguous character. Odysseus doesn’t always act in ways that appear straightforward and honorable and was not universally revered in Greece. He can be “twisty” or shifty and sometimes he seems to sacrifice others for his own benefit. The Romans especially had a negative view of him, if we can trust Virgil, who contrasted him very unfavorably with Aeneas and his pietas – duty, honor and devotion. This gives Odysseus a depth epic heroes rarely have.

Odysseus’ most important trait, however, is his mêtis, another Greek word that has no direct translation, but seems to have originally meant “magical cunning.” Mêtis refers to the ability to think creatively, subtly, ingeniously – to “turn” things over in one’s mind – to be flexible, adaptable, have foresight; to be able to (as we say today) “improvise and overcome.”

Mêtis is also the Greek goddess who embodies these characteristics. She was Zeus’ consort and when he impregnated her, it was foretold her child would be greater than its father (a common trope) so Zeus swallowed her (shades of his father’s and grandfather’s behavior). As the story goes, the baby gestated inside Zeus until he became tortured by an agonizing headache. Seeking relief, he had Hephaestus crack his skull open and Athena emerged, fully grown and already armed. Athena inherited mêtis as one of her main attributes from her mother, and Odysseus, her mortal favorite, is its embodiment among men. It is this quality that allowed Odysseus to win the Trojan War by means of a stratagem – the Trojan Horse – where Achilles failed.

Odysseus may appeal to our modern sensibilities of “brain over brawn” and “fight smarter, not harder,” but what about the ancient Greeks? Why did they pick Odysseus? Did they esteem these selfsame qualities? I bring this up because it led me to consider a theory that I thought was cute and (it might be said) had every virtue except that of being right. My thoughts ran along these lines:

Who in ancient Greece esteemed mêtis? That would be the Athenians; Athena was their patron deity and they considered mêtis to be one of their main virtues, as opposed to the Spartans, who were just good at killing people. The stories of the Trojan War were first assembled into a whole in Athens. Martin West argues the Athenians made editorial revisions to the Iliad, one of which was identifying Ajax the Greater as being from Salamis (Athens not figuring prominently in the epic). Could, therefore, the Athenians be somehow responsible for the elevation of Odysseus despite him having no ties to their city-state? The timing was tricky, but there was just enough overlap for it perhaps to be plausible.

Until it wasn’t, that is. Researching further, what is certainly a better and, I think, highly likely hypothesis presented itself. Odysseus (as I’ve noted previously) is an old Indo-European trickster figure, which accounts not only for his cunning, but his moral ambivalence; think Loki in Norse mythology. Like Loki is to Thor, he is the compliment to the peerless warrior hero, Achilles (though not so adversarial). In the Iliad, Odysseus is more noted for his wisdom, foresight and oratorical skills than his wiliness, but I make allowances for shades of difference between the Iliadic Odysseus and the original mythological Odysseus. (To be fair, he is called a man “of many stratagems” in the Iliad, but his strategic thinking ability plays little if any role in the epic.)

What is important about the mythological Odysseus is not his cunning per se, but (per Malcolm Davies, 2002) his connection with a magical horse. I embedded the following in a footnote in Wrestling with Proteus, but it’s time to surface it. Davies relates an Indo-European tradition of magical agents, such as a “mechanical” horse (the wooden horse is depicted as having mobile eyes, knees and tail, but some sources also say its eyes were lit, implying it was once thought to be “alive” in some sense); Martin West suggests it might also have Middle Eastern origins, which is certainly not contradictory. Such a magical agent was needed to overcome Troy’s invulnerable walls, which were (after all) built by Poseidon and Apollo. Virgil included this tradition in the Aeneid. In Book 2 (20–27), he told the usual story of the horse but in Book 6 (599), he wrote: “the fatal horse mounted over our steep walls.” (This is one of the editorial errors that Virgil – sadly for him, but beneficial to us – was unable to correct due to his premature death; we should be even more thankful that the Emperor Augustus prevented the poem’s destruction in accordance with Virgil’s deathbed wishes.)

Davies has suggested such horses were used in Indo-European myth to rescue captive princesses and that Odysseus once had such a horse. Thus, his elevation to the Greek’s primary hero would not be due to his mêtis, but the tradition he had a magical horse that could rescue a captive princess, in this case Helen (who, as I noted, had a tradition of being abducted). Over time, the magical horse became replaced with a ruse, and Odysseus – trickster that he was – had his mêtis brought forward to come up with the horse idea at the prompting of Athena, herself closely associated with horses.

The mythological Odysseus and the Iliadic Odysseus, along with his promotion and the horse story, again suggest that Homer’s Iliad and the mythopoetic tradition were once distinct and Homer, while aware if it, wasn’t following it. As I commented previously, if the Greeks had a practical tradition regarding Troy’s fall (as I’ll touch on in another context later), they would have had no need to resort to a magical-horse-turned-ruse to explain it.

Now, I’ll move on to the second, and somewhat more controversial, change to the Iliad: the Judgement of Paris.

The [missing] Judgement of Paris

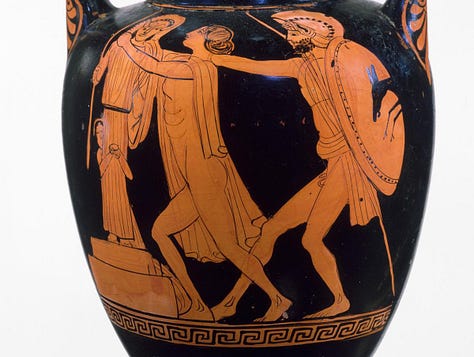

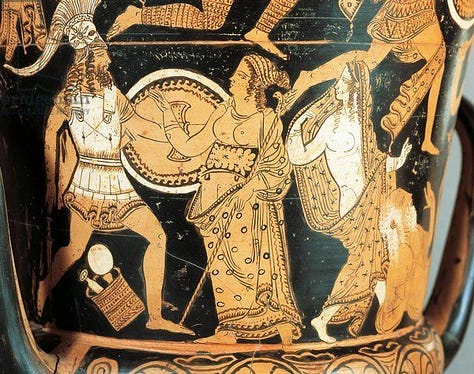

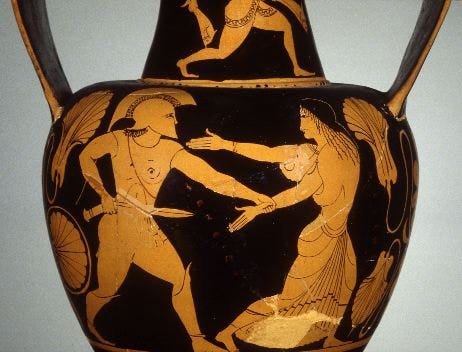

I covered some of the debate on the Iliad’s allusion to the Judgement of Paris in Wrestling with Proteus, as an example of how faith in the “Unity” affects Homeric scholarship. Here, I thought it would be useful to go into a bit more detail, particularly in one regard: the use of ancient art to support hypotheses about literary works. But first, I thought some background might be in order. So here goes…

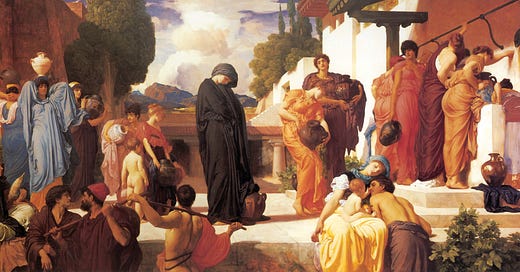

In ancient Greece beauty contests were, as we might say today, a “thing.” How far back they go is unknown. We have evidence of them in Greek vase painting, but this did not start until later in the 7th century (50 to 100 years after Homer) and there is no reason to believe they were not happening long before this, perhaps as far back as the Bronze Age. As I discussed in my essay on Helen, Bronze-Age princesses were judged on their kharis (grace, elegance and charm), kallos (beauty), and physical fitness which enhanced kléos and kudos (reputation in the eyes of one’s peers and the world at large). It would therefore be unsurprising to have contests to decide who best exemplified these virtues in the Bronze Age, just as they did much later.

This may seem rather superficial and “objectifying” to us, but the ancient Greeks took a different view. If you could approach a Greek of that era and state “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” you would be met with incomprehension or maybe a decidedly negative response. To the ancient Greeks, beauty was a gift of the gods – a manifestation of divine favor; there was no “eye of the beholder” about it, anymore than there would be for the winner of a foot race or a wrestling match. Beauty, and therefore beauty contests, had a distinct religious and sacred character.

One informative, not to say entertaining, example is reported near Syracuse in Sicily. (It’s fairly well known, but the most accessible account might be in Bettany Hughes’ Helen of Troy.) The story is that a group of Greek colonists wished to raise a temple to Aphrodite Kallipygos, literally “Aphrodite of the Beautiful Buttocks;” a popular deity at that time. There was the question as to where to place the temple. To address this, a pair of “well-rounded” farm girls were selected to “face off” (as it were) to determine who had the best “assets.” The winner was then given the honor of choosing the site of the temple. (Hughes, 118.)

We might be tempted to snicker at the prurient overtones of these proceedings and the ancient Greeks did have a robust and ribald sense of humor and fun. But this should not cause us to overlook the very real religious importance of such a contest. While it may seem a bit odd and “unserious” to our eyes, piety and fun are not always mutually exclusive and what honors the gods and is pleasing to them may also be pleasing to us. To properly understand ancient history, we must often set aside our modern perceptions.

So I think I may suppose Homer was fully aware of beauty contests (divine or otherwise) and accounts of them were part of his background. But did he include one in the Iliad? What evidence should we look for?

The first known evidence we have of the Judgement of Paris is a scene on the Chigi vase depicting Paris (labeled as Alexandros) and three goddesses. The Chigi vase is a Middle or Late Protocorinthian olpe (pitcher) dated to 650-640, and no later than 630 (Rasmussen 2016). This is 50 years or more after Homer and it might be tempting to take it as evidence of the episode being in the Iliad, since this is prior to the date of the Cyclic poems (being finalized, that is), but caution should be exercised.

Martin West believed it likely a separate poem existed the told the tale of the Judgement of Paris and the elopement, ending with the couple’s marriage in Troy. Sappho knew of such a story, as a fragment of her poetry contains a description of the wedding. While Paris and Helen running off together being the cause of the war was current in her day, this is not evidence, one way or another, of there being stories about the Judgement of Paris outside the Iliad or within it.

All that might be said is that, before the date of the vase, there was a story about a divine beauty contest and Paris may have been involved, without implying anything further. If the study of folklore and myth tells us anything, it is that there are many stories which are short and simply tell of some brief episode in a hero’s life without relating to other stories; they are standalone. There can be, and usually are, many different versions of such stories, often incompatible. (This is true even for historical figures. We might consider the examples of Daniel Boone and Davy Crocket in US history. Both are historical persons about which a collection of “tall tales,” i.e. legends, are told.) Such a story about Paris could be depicted on the Chigi vase.

Muddying the waters further, there is some question as to when the inscription was added. The Judgement of Paris is not the only divine beauty contest we know of; there is another recorded which resulted in the canard “All Cretans are liars.” So it could be that someone took possession of the vase much later, was reminded of the Judgement of Paris from the Cypria or a related source, and had it annotated accordingly.

But even if a myth existed in Homer’s day about Paris and three goddesses, and even if it related to the Trojan War, this does not mean Homer would have used it, especially if it did not comport with the tradition he derived his epic from. How we interpret the vase’s image depends on what we assume about the Trojan War legend in the first half of the 8th century and the Iliad’s place in it. So the vase is really no help to us, except perhaps as a caution about being careful of going-in positions based on untried presumptions. That brings us to the textual debate, which can be addressed briefly.

C. J. Mackie discusses a detailed description by Nicholas Richardson of the debate on the Judgement of Paris in Book 24. Mackie quotes a number of the objections Richardson cites: 1) all the gods are said to agree, then three of the most powerful are excluded, which is “absurd”; 2) the Judgement of Paris is not mentioned elsewhere in the Iliad which is inconsistent with its presumed importance; 3) words are misused in two cases. Mackie remarks that these are “by no means” the only objections to the passage “all of which are cited by Richardson.” He then adds an additional concern that Poseidon’s antipathy toward the Trojan’s stems from Laomedon’s treatment of him and Apollo, not a “divine beauty contest.” (Mackie, 3).2

As I noted in my discussion of the Unity, Mackie goes on to say that the passage’s defenders do so on the basis of its relevance to the “broader context of the whole poem” – in other words, the Unity. If the Unity is not operative, the argument for the Judgement of Paris being in Homer’s Iliad falls apart. Martin West sided with the textual critics and said it’s an interpolation. On this basis, I think it’s highly likely that the allusion to the Judgement of Paris in Book 24 was added to make the Iliad more consistent with the mythopoetic tradition.

The Sack of Troy

For me personally, the oddest thing about the Iliad is the sack of Troy: it’s hardly mentioned. Yet the sack of Troy – or the Sack of Troy – is the great fact of the whole story. As I’ve pointed out, it’s been called the Legend of the Fall of Troy; the sack is the doom that hangs over everyone in the Iliad and drives the perception of the whole story and even archaeology. There is hardly an episode in the Iliad that isn’t interpreted in view of the sack.

So why is it all but ignored in the Iliad, and why is the story after the Iliad so confused? It is understandable that Homer ends his epic before the city falls, but consider what happens next. It takes two more poems before we approach the sack. Having killed Hector, Achilles is supposedly facing imminent death due to the prophecy but instead we get Penthesilea, a trip to Lesbos to be purified, and Memnon (with that repeated prophecy) before he meets his end.

Then the real “fun” begins. The Greeks – having killed Hector, having killed Penthesilea and having killed Memnon, great champions all – are no closer to taking Troy. They manage to capture Priam’s son Helenos (a seer) who helps them lay out a plan to accomplish that (perhaps thinking it’s beyond their capabilities; he has a point): they have to get Achilles’ son Pyrrhus/Neoptolemus.3 They need to retrieve Philoctetes, who has been languishing on an island for ten years with Heracles’ bow after being bitten by a snake. They must steal the Palladium and fetch Pelops’ bones. Having done all that (and killing more Trojan allies), they are still nowhere near taking Troy. Finally (was her bingo card full?), Athena whispers to Odysseus to make the wooden horse happen, and the city is sacked with an abundance of gratuitous mayhem, and related in the Iliou Persis.

What has always struck me as peculiar about all this rigmarole is that Patroclus came within an ace of taking Troy in the Iliad; Apollo had to intervene and knock him off the wall three times before Hector can kill him. Achilles was on the verge of taking Troy after killing Hector, but unaccountably decides not to and returns to the Greek camp. He was on the verge of taking Troy a second time after killing Memnon, but Paris killed him first with an assist from Apollo. At that point, the story loses all coherence as the box checking starts.

When I considered this, the impression I got was not that I was reading the “Legend of the Fall of Troy,” but the “Legend of the Repeated Failure to take Troy”. At this juncture, I started to pay careful attention to how Homer speaks of the fall of Troy in the Iliad. What struck me is the degree to which the mentions of Troy’s fall are conditional. Homeric scholars have characterized this as “delusional,” and while that judgment is not easily dismissed, I have trouble squaring it with the explicit mentions of the sack in the epic. There are only two and since the second depends on the first, they really count as one, and I already alluded to them in my roadmap.

The passage in question is at the beginning of Book 12. It starts with Patroclus tending to his comrades’ wounds in his shelter while the battle rages outside: “So the valiant son of Menoetius tended wounded Eurypylus in his shelter; and in massed throngs the men fought on, Argives and Trojans.” The next line, however, launches into a long discourse on how the gods intend to destroy the wall around the Greek camp because the Greeks failed to properly sacrifice to them when they built it. Then the text says Troy will fall:

As long as Hector was alive and Achilles filled with wrath 10

and the city of lord Priam was not sacked, so long the great wall of the Achaeans stood firm. But when all the best of the Trojans were dead, and many of the Argives killed, while some survived, and the city of Priam had been sacked in the tenth year, and the Argives had set out in their ships to their beloved fatherland, then did Poseidon and Apollo devise a plan to level the wall, channeling the might of the rivers, all the rivers that stream from the hills of Ida to the sea – Rhesos and Heptaporos and Karesos and Rhodios… 20. (Caroline Alexander’s translation.)

After more details on how the wall will be destroyed, the text concludes with a strange and awkward “meanwhile back at the ranch” splice to the ongoing action:

30…

These things Poseidon and Apollo intended in time to come; but for now battle and the din of war blazed round the well-built wall, and the timbers of the ramparts resounded as they were struck… 40.

(Caroline Alexander’s translation; emphasis added).

This digression is strange; it has nothing to do with the narrative, coming out of the blue simply to make the point the “well-built” wall will come down after Troy is sacked. It is out of place, reads in a different, more passive voice, and ends with the weak statement that these things are “intended in time to come” with the maladroit splice. Remove it, and the passage reads like this:

So the valiant son of Menoetius tended wounded Eurypylus in his shelter; and in massed throngs the men fought on, Argives and Trojans. Battle and the din of war blazed round the well-built wall, and the timbers of the ramparts resounded as they were struck; Argives broken under the lash of Zeus, cowering in the hollow ships, were stayed in dread of Hector, violent master of the rout; he, as before, fought on, like a whirling storm wind.

That reading is simple, coherent and consistent, and it maintains Homer’s voice. Could Homer have composed such an non sequitur?

Personally, I doubt it. However, I could find no one questioning this passage. Martin West comes closest: he points out that being forward-looking is “abnormal in terms of Epic practice and distorts the sequence of thought” (West 2011, 263). He then points out that in Book 15 (361-6), “Apollo will knock it [the wall] down like a sand castle; there seems to be no consciousness there of the annihilation planned for after the war.” West opines that the passage was a “late invention by Homer” and that it and a related passage about the wall in Book 7 (442-64) “are expansions.” He says further that the passage seems “inspired by the Mesopotamian flood myth” and may also show awareness of the destruction of Babylon by Sennacherib in 689.

My feeling is that had West not believed in the Unity (which I think he did), his assessment that the passage was added late would likely have become added by a later author. A key piece of evidence is the names of eight rivers mentioned in the passage (lines 20-22). He points out that of these eight, only the Scamander and Simoeis are regularly mentioned in the Troy epics. Another, the Aisepos which flows into the Sea of Marmara “some 80 miles east of Troy is the only one mentioned elsewhere in the Iliad.”

Tellingly, all of the rivers except the Karesos are in Hesiod's “Catalog of Rivers” in the Theogony (lines 337-345), making that the likely source. West further points out that the four rivers named in line 20 were “problematic for ancient scholars,” there being “no guarantee” they were even in Anatolia. He comments that the Rhodios and Heptaporos are listed as Thracian rivers in the Theogony (341), and Rhesos and Karesos “also sound like Thracian names.”

The Iliad makes clear that Homer was intimately familiar with the area around Troy. That he would have included rivers in Thrace in the region’s geography seems nearly inconceivable. That the rivers appear to have come from Hesiod, and accepting West’s suggestion that the passage’s author knew about Sennacherib’s destruction of Babylon, puts the creation of this passage well after Homer. West has used this passage (in part) to date the Iliad later than other scholars, but I view that as a rare misreading by him. Accepting the consensus date of 740-700 and this passage as an interpolation to get the sack of Troy explicitly into the epic resolves the issue.

The final bit of evidence for this passage being an interpolation is the use of the word “demigods,” which occurs only here in the Iliad. Hesiod and later poets use it though, again suggesting whoever added this passage relied on Hesiod as his source and slipped in a word Homer never used.

The other explicit reference comes when Zeus is talking to Hera, giving her a dressing down in Book 15. After he gives us a quick summary of Patroclus’ combat and death, this line appears:

And from that point, then, without respite, I will effect a retreat from the ships, all the way until that time the Achaeans 70

capture steep Ilion through the designs of Athena.

(Caroline Alexander’s translation; emphasis added).

Here again, we have foreshadowing of Troy’s fall dropped in the midst of a discussion about something else. The idea Troy will be captured “through the designs of Athena” is nowhere else alluded to in the Iliad, and clearly points to her suggesting the Trojan Horse ruse to Odysseus. This dovetails with Book 10, inserted to elevate Odysseus and his mêtis, a theme that is otherwise missing from the Iliad, and looks like an interpolation to introduce the idea that Troy will fall by mêtis, not might, which is crucial to the mythopoetic tradition.

Next, the passage appears to be a contradiction, as in this wording Zeus is saying the fall of Troy is part of his promise to Thetis. It wasn’t and again, the passage is clearer and more consistent with the problematic text removed:

… let him [Hector] roll the Achaeans back again after stirring abject panic, so that they fall fleeing into the many-benched ships of Peleus’ son Achilles.

Before that I neither stop my anger nor will I permit any other of the immortals to defend the Danaans here at Troy, not before the wish of the son of Peleus is fulfilled, as I first promised him, nodding my head in assent, on that day when the goddess Thetis clasped my knees entreating me to honor Achilles, sacker of cities. (After Caroline Alexander’s translation.)

Now Zeus is making a clear, consistent statement: he will not allow the other gods to defend the Greeks until his promise to Thetis is met – that they restore Achilles’ honor: “Do you now revenge him, Olympian Zeus, all-devising; give strength to the Trojans until that time the Achaeans recompense my son and exalt him with honor.”

From all this, it appears the passages were added to foreshadow the fall of Troy which is otherwise ambiguous in the Iliad. In the rest of Homer’s epic, his statements about the fate of Troy are consistent with this exchange in Book 8:

Hera addressed Athena with a word: “O, dear daughter of Zeus who wields the aegis, I can no longer allow us two to battle Zeus for the sake of mortals. Let one of them perish, let another live, as his luck may be. And let Zeus pondering those plans of his 430

decide for Trojans and Danaans, as is his right.” (Caroline Alexander’s translation.)

So what is Homer up to here? Is he, in effect, talking out of both sides of his mouth?

I don’t think so. Homer is clearly aware of the tradition of Troy’s fall, so he incorporates it, but in a special way. In doing so, I feel he accomplishes something markedly profound: he shows us the sack in gut-wrenching clarity through the words of Priam and his family – especially the women, who have the most to lose – but by rendering it conditional, he keeps us in suspense, stretched wire-tight between horror and hope, however dimly it flickers.

Like the people in his poetry – and through them – he puts us on Zeus’ golden scales. The fate of Troy hangs in the balance, as it does for everyone. Homer’s message is (as we know) that mortality is inescapable – they always tip the same way in the end.

Works Cited

Of special note, these online lectures Prof. Luttrell are very valuable:

The Iliad (www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DHgPePIFhk)

The Odyssey (www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJOaItUjRow)

The Aeneid (www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLjRQKwDKBk)

Davies, Malcolm. “The Folk-Tale Origins of the Iliad and Odyssey.” Wiener Studien 115 (2002): 5–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24751364.

Dué, Casey. “Maneuvers in the Dark of Night: Iliad 10 in the Twenty-First Century.” Homeric Contexts: Neoanalysis and the Interpretation of Oral Poetry (eds. F. Montanari, A. Rengakos, and C. Tsagalis), (Walter de Gruyter, 2011), pp. 165–173. The Center for Hellenic Studies. chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/casey-due-maneuvers-in-the-dark-of-night-Iliad-10-in-the-twenty-first-century/#n.2.

Hurwit, Jeffrey M. “Reading the Chigi Vase.” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. 71, no. 1, 2002, pp. 1–22. http://doi.org/10.2307/3182058.

Hughes, Bettany. Helen of Troy, Goddess, Princess, Whore. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2005.

Mackie, C. J. “‘Iliad’ 24 and The Judgement of Paris.” The Classical Quarterly 63, no. 1, (2013): 1–16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23470072.

Nagy, Gregory. “Pindar’s Homer is not ‘our’ Homer.” Classical Inquiries. December 24, 2015.

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/pindars-homer-is-not-our-homer/.

Rasmussen, Tom. “Interpretations of the Chigi Vase.” BABESCH 91 (2016): 29–41.

Rasmussen, Tom. “Paris on the Chigi Vase.” Cedrus 1.1 (2013): 55–64.

West, Martin. The Making of the Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Footnotes

In the Iliad, Odysseus’ martial exploits are relatively modest. It is in the Cyclic poems that his warrior status is elevated to the front rank, particularly in regards to the fight for Achilles’ body, where he is awarded battle honors over Ajax, previously said to be the Greek’s best warrior after Achilles.

Nicholas Richardson, The Iliad: A Commentary, Vol. 6, Books 21–24, Cambridge, 1996, 276ff.

The Cypria says he was first called Pyrrhus and Phoenix gave him the name Neoptolemus. This suggests audiences knew his original name from an older tradition, thus requiring explanation in the Cypria. Neoptolemus means “new war” which hints that his single mention in the Iliad is also an interpolation. West believed that to be the case.

I love the title of this essay! I'm super-impressed by your extensive research and knowledge. It was all fascinating bu tI was most enthralled by the part about Odyssesus and metis. Great stuff!

I love the phrase, “poetics of ambush.” Another fascinating read!