The essays I’ve been posting here on Substack are in support of my work in progress: The War for Helen: A Reexamination of History’s Most Misunderstood Conflict. As a crucial part of this exercise is to examine how we got the story of the Trojan War (I prefer to call it the War for Helen, but will stick to the more familiar name for now), I decided it might be a good idea to have a roadmap to lay out how my research indicates that story evolved, so here it is. (The graphics are not stellar but I trust they will get the job done.) My work relies heavily on the scholarship of Martin L. West, whom I consider to be the preeminent authority in the field for at least the past half century. I have, for completeness, included references from other scholars whose views diverge from his.

I initially intended this essay to be much shorter, but as it didn’t work out that way, I’m posting it in sections. This is Part 1; it introduces the basic concept of my roadmap and covers the first phase of it.

Introduction

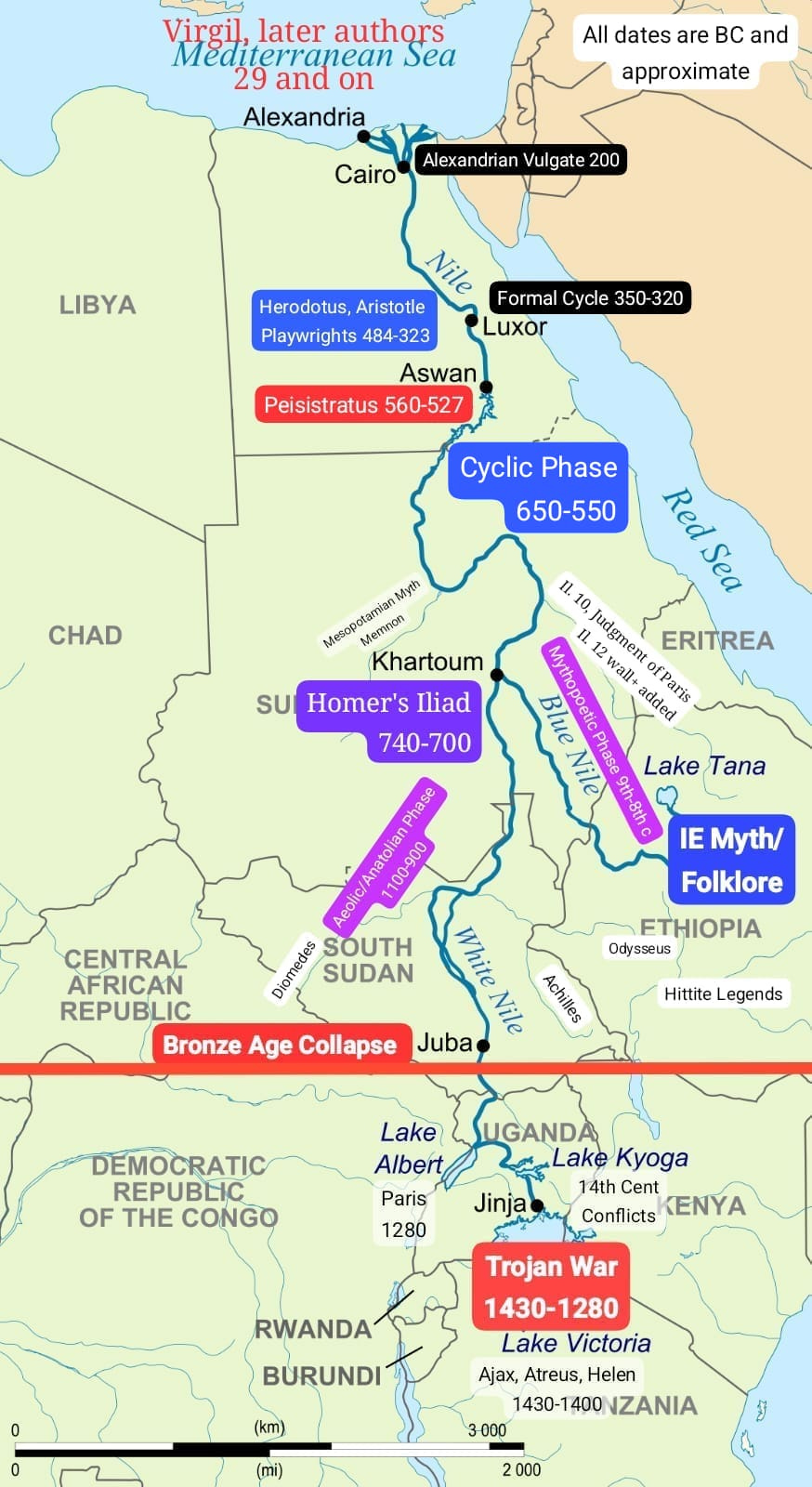

Gregory Nagy formalized his theory of how epics develop in his evolutionary model (I provided a brief synopsis of it in my essay, Homer and the Written Word), and Jonathan Burgess offered up an “arboreal” simile when he said if the Trojan War legend were a tree, the Iliad and Odyssey would be “a couple of small branches” while the Cyclic poems would be “somewhere in the trunk.” (The Cyclic poems are the six lost works that complete the legend.) Inspired by them, I came up with a “hydraulic” model for the legend’s evolution, based on the idea of rivers and deltas, which I’m introducing here. This discussion is not comprehensive and still in work; I’ll get deeper into each phase in the future and (hopefully) correct whatever misperceptions I currently have and mistakes I’m making.

My purpose in exploring the legend’s evolution is not only to try to understand that in its own right (as important and fascinating as it is) but also to work backwards to the legend’s origins – its prehistory, if you will; an endeavor eminent scholars have sternly warned against1 – in an attempt to discern (to the extent possible) the legend’s original plot and purpose, and how those might have derived from historical events. It’s a tall order and I’m not sure I’m entirely up for the task, but I will “endeavor to persevere.”2

Since I based my “model” (being generous) on rivers and deltas, I’ll start with a brief bit of context (because I like to do that). Onwards and (again, hopefully) upwards…

Keywords: the Trojan War, the Iliad, the Homeric poems, the Cyclic poems, Homer, Literary models.

Acknowledgements: I am deeply indebted to Cynthia Gralla of Royal Roads University for her kind assistance and support in the creation of my work, including help with research, excellent editorial suggestions and many insightful comments. I also received much-needed help from Eric Luttrell of Texas A&M, who gave me the idea of rivers and deltas, and was indispensable to formulating my arguments and correcting my many unfounded suppositions. They have saved me from many embarrassing errors. Those that remain are solely my own.

A “Hydraulic” Model

In the latter half of the 19th century, one of the endeavors that captured public imagination, especially in Great Britain but also elsewhere, was the search for the source of the Nile. It was seen as a romantic, even heroic, adventure.3 A number of celebrated explorers undertook it, some of them gave their lives for it and while they made important discoveries, including Lake Victoria, they never did find what they were looking for. In fact, the source of the Nile as they imagined it has never been found, because as a practical matter, it does not exist. The Nile is made up of tributaries that are fed by streams, that are in turn fed by smaller streams originating in springs and so on, all distributed over a vast area, which in the aggregate might be described as the source of the Nile.

At the mouth of the Nile the opposite happens. The river splits into a myriad of smaller channels that spread out over the Nile delta before it flows into the Mediterranean. These are a common feature of rivers: they begin as a multitude of sources and end by spawning a network of channels. A similar thing is true of myths and legends: they have their origins in the vast watershed of oral tradition; countless stories that can come together into a grand story, a literary Nile, that eventually assumes the character of a “fixed” text and then goes on to inspire myriad subsidiary works, a literary delta. All these stories thereby enter the vast sea of our historical consciousness and become part of our cultural heritage.

Nagy’s evolutionary model explains this process and has been vastly influential in Homeric studies. However, I believe it may require some expansion. His model explains the situation in a “state of nature,” where oral works are composed and evolve “organically.” Putting it another way, when people enter my (notional) landscape and start damming rivers, rerouting streams, lining watercourses and digging canals, they alter the “state of nature” according to their own plan. A model that only accounts for how rivers flow, merge and divide without such intervention is only addressing part of the situation.

I submit that the story of the Trojan War is such a case: it represents a hybrid of myth and folklore, which are inherently “organic,” and what I called “epic-historical” poems, which are more akin to the Deeds of Kings recorded in Near Eastern Bronze Age cultures. Folklore is therefore fluid and the “wandering minstrel” who entertains the populace is free to elaborate on the stories as his audience desires, and the preferred version of a myth or folkloric tale will likely vary by location.4 The Nart sagas of the Caucasus are prime examples of this. In contrast, the bard singing of “great deeds” in a king’s feasting hall is obliged to stick to the “facts”; these songs are not composed for the people, but on behalf of rulers and they are the audience the bard must respond to.

Thus, Nagy’s model seems less apt for “royal bards” performing the deeds of kings than for the “wandering minstrel” entertaining people with folktales.5 Further, while Nagy correctly points out that oral recitations have authority over written texts in predominately oral cultures, not all actors involved in the creation of the Trojan War story are from such cultures. The Bronze Age societies of Anatolia, Egypt and Mesopotamia did view written texts as authoritative and they make this explicit: treaties were written in several languages so all parties could read them, laws were carved in stone and erected in public spaces where they could be read; a Hittite king directed that the treaty he concluded with a vassal ruler be read out to the latter three times a year so he would know its contents exactly.6 Thus, people had been at work in this “land” long before any hint of the Trojan War legend existed.

So it seems reasonable that this attitude would have carried over to texts of Anatolian versions of the Trojan War legend and could have affected the attitude of Iron-Age Greeks, enhancing the preservation of the Anatolian side of the story and affecting how it was used. I hold that Nagy’s model is therefore not the whole picture, and also does not include (in fact, rejects) the most important actor of all in the formation of the Trojan War legend.

For into this rich and varied “landscape” of myth and deed, stepped a figure of such extraordinary genius that he gathered up, almost like the gods he sang about, many rivers, streams, canals and other watercourses – some wild, some carved and lined with stone by his predecessors – and brought them all together into a single river, Amazonian in its proportions; so mighty that it obliterated nearly all trace of the tributaries that fed it and transformed our impression of the landscape he worked in forever. That genius was the poet we call Homer.

Romance (which the Oralists warn us about)? As I said before: “There is indeed something romantic about this kind of genius, but that is not incompatible with it being true.” I will also repeat Caroline Alexander’s observation on the subject:

The Iliad, one must bear in mind, is not only informed by a long tradition, it is the last iteration of that long tradition. There is no other Iliad after the Iliad. Did centuries of tradition simply end because the performance of the last poet, Homer, was so exceptional as to deter all other competing bards and versions? Or had the tradition, as an oral process, already ended, allowing an individual poet – Homer – to address the inherited material with untraditional liberty?

I think he did. But what happened when this “river” – the Iliad – changed (or evolved) as it made its way from his day to ours, forming as it did so, its own vast “delta”? There are two parts to that: the anatomy of the Iliad itself, which Martin West described (I will attempt an overview at a future point), and the “geography” in which the Iliad resides, according to my “hydraulic” model. Let’s look at that.

The map above illustrates my initial conception of how the Trojan War legend evolved. I picked the Nile as my basis because of its historical importance and also because, happenstantially, its geography fits my “model” to a T (almost too well, to be honest). I’ll describe each part of the process and list references I found particularly helpful to understanding it (independent of whether I embrace all their conclusions or not). I’ll list the most accessible references first; usually books aimed at nonspecialist readers that are available in libraries. I’ve also included specialist papers when I haven’t found sources intended for a more general readership that provide the same information; these are typically available online at sites like JSTOR. (Anyone who wants to dig deeper will also find them useful.) The references include their own lists of sources, which are often quite extensive, and at the end of my final installment will be some suggestions for further reading. With that introduction, here goes…

1. Trojan War and Indo-European Myth/Folklore

I start my process at two points: the historical Trojan War, which I sited at Lake Victoria, and the vast body of Indo-European myth and folklore, which I placed in the Ethiopian highlands around Lake Tana.7 From this region, we get Helen (the Sun Maiden), her brothers (the Divine Twins), the Judgement of Paris, Odysseus (a trickster figure from ancient myth), the Trojan Horse and likely Hector, who has been suggested to originally be a Greek folk hero, possibly associated with Thebes. Achilles and Diomedes also have their origins as folk heroes (Diomedes may have been a god), but could have historical persons who inspired their presence in the legend. Agamemnon and Menelaus appear to be figures from a traditional Indo-European story about brothers reclaiming an abducted princess. The other mythological and folkloric elements in the legend all originate here, many (including the Sun Maiden) going all the way back to the proto-Indo-Europeans.

Lake Victoria represents the first phase of the conflict: the Aššuwa rebellions and campaigns of Atrius (Attarissiya). A Theban princess who married into the Aššuwan royal house, my notional Helen, and a Greek hero who appears in the Iliad as the Greater Ajax are key personages.

Lake Kyoga denotes the middle phase of the war. A Greek hero represented by Diomedes may have been a major figure in the legends of this period. Kukkunnis, the Trojan king who is possibly linked to the mythical Trojan hero Kyknos is from this period, along with any historical figures whose exploits may be assigned to Achilles and possibly to Hector, although he may have been added to the legend much later and have no historical counterpart.8

I selected Lake Albert for the last phase of the war, which ended in 1280 with the Alaksandu Treaty. Alaksandu and Piyamaradu are the major historical figures. Paris/Alexander is attested as Alaksandu; Piyamaradu may have inspired major parts of Achilles career. There is the possibility of a Greek princess who married Alaksandu and added to the legend of Helen. This concludes the first phase of my model.

References for the folkloric basis of the Trojan War legend:

Davies, Malcolm. “The Folk-Tale Origins of the Iliad and Odyssey.” Wiener Studien 115: 5–43. 2002. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24751364. (Lots of information I’ve not found elsewhere.)

Mallory, James. In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Thames & Hudson. 1991. (General information on Proto-Indo-European and Indo-European culture.)

West, Martin. Indo-European Poetry and Myth. OUP Oxford, 2007. (Great if you can get it from a library.)

West, Martin. Immortal Helen (Lecture). 1975. (Excellent, if you can find it! Check https://search.worldcat.org/title/2646902.)

Jackson, Peter. “Light from Distant Asterisks. Towards a Description of the Indo-European Religious Heritage.” Numen, vol. 49, no. 1, 2002, pp. 61–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3270472. (Information on Proto-Indo-European myths.)

Colarusso, John. Nart Sagas from the Caucasus: Myths and Legends from the Circassians, Abazas, Abkhaz, and Ubykhs. Princeton University Press, 2016. (An example of folktales and myths in oral tradition prior to amalgamation; also shows tie-ins to well-known Greek myths).

References for the Trojan War:

Cline, Eric. The Trojan War: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. (An excellent discussion of the Trojan War; very much to the point.)

Latacz, Joachim. Troy And Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery (translated by Kevin Windle and Rosh Ireland). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Strauss, Barry. The Trojan War. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006. (The best recent book on the Trojan War, which inspired my research.)

Strauss, Barry. “Episode 1: Achilles.” Antiquitas, season 1, episode 1, Barry Strauss Podcast, November 10, 2018. http://barrystrauss.com/podcast/page/3/. (Excellent and entertaining.)

Strauss, Barry. “Episode 2: Helen of Troy.” Antiquitas, season 1, episode 2, Barry Strauss Podcast, November 12, 2018. http://barrystrauss.com/podcast/page/3/. (Also excellent and entertaining.)

Korfmann, Manfred. “Was There a Trojan War?” Archaeology Magazine, vol. 57 no. 3, May/June 2004. http://archive.archaeology.org/0405/etc/troy.html. (Great insight from a man on the site.)

West, Martin. “Atreus and Attarissiyas.” Glotta 77, no. 3/4 (2001): 262–66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40267129. (Explains the link between Attarissiyas and Atreus; important to understanding the historicity of the Trojan War.)

Beckman, Gary. Bryce, Trevor. Cline, Eric. The Ahhiyawa Texts. Netherlands: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011. (All known texts between the Mycenaeans and Hittites during the Trojan War period.)

Bryce, Trevor. Warriors of Anatolia. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019, 2023. (Basic background on the Hittites.)

Woudhuizen, Fred. The Luwians of Western Anatolia: Their Neighbours and Predecessors. Archaeopress, 2018. (Basic background on the Luwians, including Trojan figures in the Trojan War.)

Nagy, Gregory. “Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology XV, with a focus on Hēraklēs of Tiryns as military leader of the Mycenaean Empire.” Classical Inquiries. Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, 2019.10.31. http://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively-about-greek-mythology-xv/. (Possible mythological tie-ins relating to the historical Trojan War.)

2. Bronze Age Collapse

The Bronze Age collapse separates the era when the poems may have been “deeds” of historical figures (epic-historical) from the later eras when they moved into the realm of legend. The Bronze Age collapse did not affect the folkloric branch of the Trojan War legend, and is included only as a historical marker.

References for the Bronze Age Collapse:

Cline, Eric. After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Cline, Eric. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and Updated. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Both of these books are readily available and invaluable for understanding the Bronze Age Collapse and its aftermath.

This is the end of the first installment. Part 2 coming soon…

Footnotes

But as I said in my introductory essay, nothing ventured, nothing gained, etc.

I lifted this line, which I love, from a short soliloquy by Chief Dan George, in The Outlaw Josey Wales; it’s a rather trenchant commentary on the whole situation between the US government and the native American populations in the late 19th century, and on the way governments all too often operate in general.

In the same vein as the race to the South Pole would later be seen in the “Heroic Age of Antarctic (or Polar) Exploration.”

Studying Greek myths, one might be forgiven for thinking every town and hamlet in Greece had its own version, and that might not be far wrong.

I’m using the terms “wandering minstrel” and “royal bard” somewhat anachronistically, although “bard” and “minstrel” are common in Homeric translations. I do not mean to imply that these are separate poets, only separate functions; any poet may perform either office as the required. Demodocus, who features in the Odyssey, is a classic prototype of such an individual.

Trevor Bryce elaborates on this in his 2019 book, Warriors of Anatolia. He relates how that when diplomatic agreements were presented to the king, the visiting envoy would recite the message from his overlord while a member of the king’s staff read along on a written copy of the message that had been recorded as part of the negotiations. The visiting envoy was expected to have the text of the agreement perfectly memorized. If there were any discrepancies between the oral and written versions, it was a serious matter and the envoy could pay with his life. No “composition in performance” here!

Using two major lakes seemed like a good starting point for a hydraulic model.

Martin West comments that the identification of Hector as the Trojan who kills the first Greek ashore in the Cypria is “no doubt secondary” – this person is left unnamed in the Iliad. This implies either the composer/compiler of the Cypria knew of an older tradition that Homer was either unaware of or chose to ignore, or made this change himself to boost Hector in the legend. There is no way to tell and according to ancient sources, four other candidates exist (West 2011, 120). This highlights the challenge of drawing conclusions about how various traditions may have originated.

I’m honored by the shout-out!