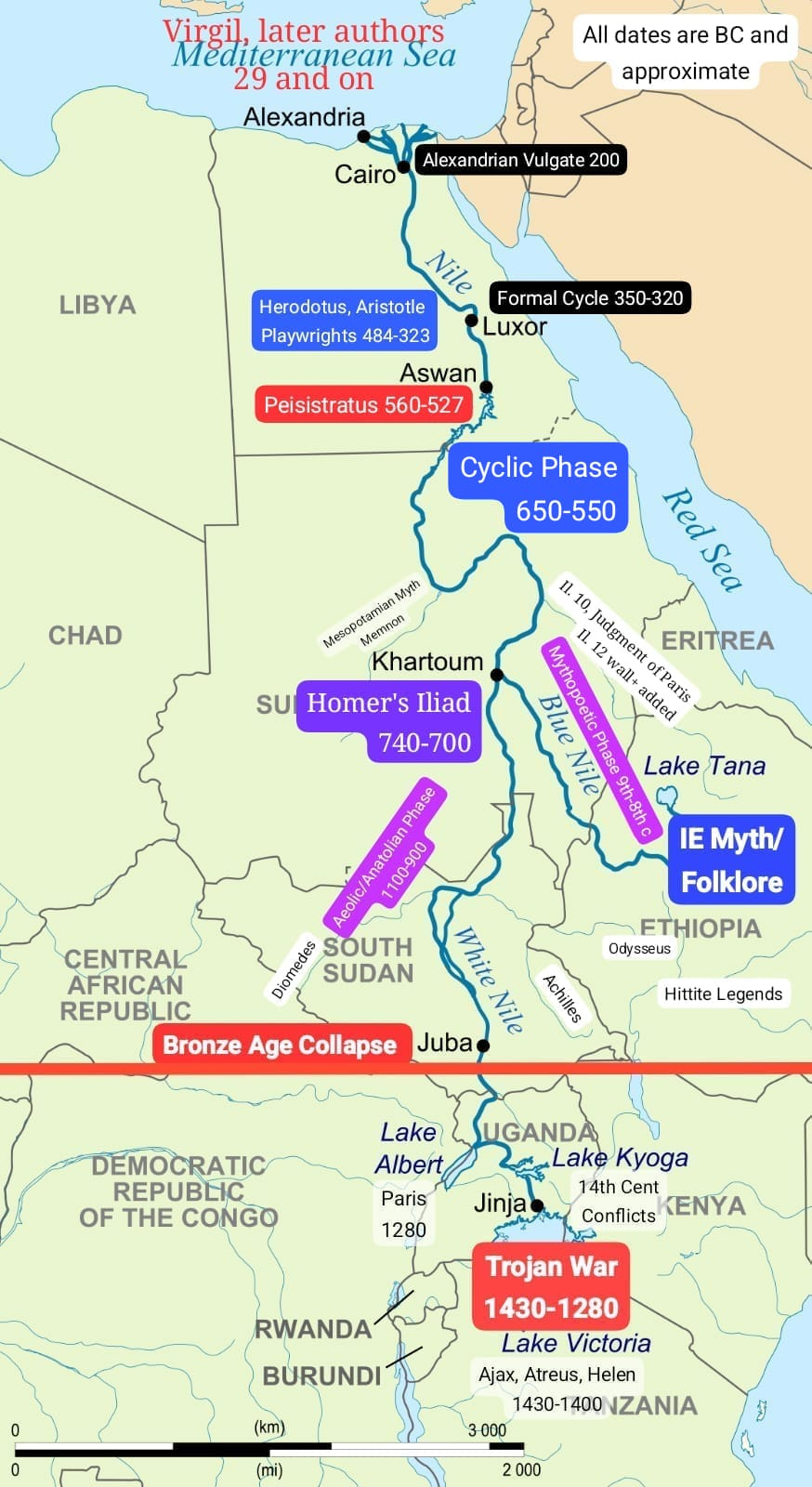

In this final part of my proposed roadmap to the evolution of the Trojan War legend, I discuss the Cyclic phase, which occurred from about the mid-7th century to the mid-6th century, amalgamating Homer’s Iliad with the Mythopoetic poems into one tradition. Thereafter, the stories of the Trojan War became assembled into “cycle,” first in Athens under Peisistratus or his son, between 560 and 527, and finally, in a formal sense, during Aristotle’s day, around 350-320. This post-Cyclic period (roughly 520-300) saw another great creative outburst related to the Trojan War; art, plays and poetry. Much of the surviving material about the legend dates from this period.

In the centuries after this formal cycle had been established, the six Cyclic poems lost their reputation; after 200 they were increasingly known from prose summaries and by 200 AD, their texts seem to have almost entirely disappeared, leaving just by synopses, descriptions and commentaries; only the Iliad and the Odyssey survived beyond this point as entire poems. The 2nd-century authors, Proclus and Apollodorus, created important summaries of the Cyclic poems which combined with the Iliad and the Odyssey and a vast array of other, often fragmentary, sources give us the Trojan War legend as we know it today.

Keywords: the Trojan War, the Iliad, the Homeric poems, the Cyclic poems, Homer, Literary models.

Acknowledgements: As always, I am deeply indebted to Cynthia Gralla of Royal Roads University for her kind assistance and support in the creation of my work, including help with research, excellent editorial suggestions and many insightful comments. I also received much-needed help from Eric Luttrell of Texas A&M, which was indispensable to formulating my arguments and correcting my many unfounded suppositions. They have saved me from many embarrassing errors. Those that remain are solely my own.

6. The Cyclic Phase.

The Cyclic Phase is key to our current perception of the Trojan War legend; the most important part of its evolution after the creation of the Iliad itself. I’m using the term “cyclic” in the sense Martin West does in his 2013 book, The Epic Cycle: poems that are meant to fill out the story in reference to either the Iliad or the Odyssey or extend them, rather than stand alone as complete epics. It is here the legend went from being disparate tales to a (more or less) coherent whole or “cycle” comprised of the Iliad, Odyssey, and the six lost cyclic poems: the Cypria, Aethiopis, Little Iliad, Sack of Troy, the Nostoi (The Returns), and the Telegony.1 The idea of these eight poems being brought together into an ordered series would not take shape until around the end of this phase (550) and their being a cycle wouldn’t be formally expressed for another three centuries. It was in no sense an organized process; it took place over nearly a century and across the Greek world, and the poems show inconsistences and sometimes overlap. (For some perspective, the interval between the Iliad’s composition and the time the Trojan War legend became formally arranged into a cycle is about the same as the timespan between us and Shakespeare, and encompassed a pivotal period in history.)

The cyclic process began after the Iliad and the Trojan War tales from the Mythopoetic tradition became sufficiently popular throughout the Greek world that they began to interact and inspire a desire to tell “the whole story.” In my notional representation, I’ve assigned this point to Khartoum, where the White Nile and the Blue Nile merge.2 The beginning of the cyclic process itself, I’ve placed later at the 6th cataract (a cataract seemed like an appropriate symbol for it). It would have been facilitated by the spread of writing, which made it easier to combine diverse oral stories and (as Martin West points out) allow them to grow to “prodigious” lengths (West 2013, 17), and also by festivals and poetic competitions, which had long played a large role in both the dissemination and composition of poems, being a vehicle by which poets could interact and influence each other; perhaps even (in a sense) collaborate.

My 650 date is fluffy; the earliest poems – the Odyssey, Aethiopis, Nostoi and the Sack of Troy (Iliou Persis) – probably didn’t reach a form close to what we know today until roughly 600 or a bit earlier, though “prototypes” would have existed before then. The reason is that the Odyssey and Aethiopis show awareness of Egypt, which the Iliad does not.3 The Greeks set up a trading post at Naucratis around 610; this is the earliest confirmation we have of their reestablishing contact with Egypt, but they must have become aware of the kingdom somewhat earlier. That awareness would have taken some time to filter into literary works, however, so a safe guess might be that the Odyssey and the Aethiopis couldn’t have been finished much before that time, and could be later.

The Nostoi shows signs of being contemporary with the Odyssey (itself technically a nostoi) and they may even have been composed with knowledge of each other. The Sack is more questionable; the balance of evidence suggests it is an earlier work, but there are a few indications it could have come after the Little Iliad. The Cypria appears to be a later work, along with the Little Iliad, and the Telegony, the sequel to the Odyssey comes last, around 550. That completed the cyclic process as we know it.

In addition to being developed at different times and places, the Cyclic poems differ in composition. The Aethiopis, Cypria and Little Iliad are mainly compilations of older material: the Aethiopis combines an ancient legend about Achilles’ encounter with the Amazon queen, Penthesilea, with an adaptation of the pre-Iliadic account of his death. West argues it was composed as a continuation of the Iliad (as opposed to a sequel), meant to pick up the story seamlessly after Hector’s funeral. Changes Homer made in the Iliad regarding Achilles’ death required its composer/compiler to introduce a new character into the pre-Iliadic account; this is Memnon, the king of Aethiopia, which I indicate with a tributary, the Wadi el Milk.

What follows is a recapitulation of the end of the Iliad with the names changed: Hector becomes Memnon, complete with a repeat of the prophecy that if Achilles kills Hector, he will die (which in the Aethiopis, he does), and Patroclus is replaced by Antilochus, now presented as Achilles’ “best friend” whose death at the hands of Memnon moves Achilles to ignore the repeat prophecy and kill Memnon. Other scenes that appear in the Iliad are also told (or retold) in the Aethiopis: King Nestor’s rescue after his chariot is disabled (by Diomedes in the Iliad and Antilochus in the Aethiopis), and scholars believe Zeus weighing the fates of Achilles and Memnon (as he does with Achilles and Hector in the Iliad) also appears in the Aethiopis (this scene is well attested in Greek artwork). The funeral of Patroclus in the Iliad seems to have been modeled on the pre-Iliadic funeral of Achilles and the Aethiopis restores it to the narrative.

The Aethiopis ends with Ajax’s suicide following the dispute over Achilles’ armor and his funeral.4 West contends the poem doesn’t point to a sequel or any further treatment of the war; its purpose was only to complete the story of Achilles, which it does. But it does so not merely as an extension of the Iliad, but also a sort of correction to the Iliad, restoring parts that Homer left out when he decided to change the meaning of the story he inherited. (This is a topic I will enlarge upon in a later essay, as it addresses the heart of my research.)

The Cypria approached the story of the Trojan War from the opposite end: it tells the events leading up to the Iliad, and does so in a notably disunified manner. It introduces the Plan of Zeus, based on a Mesopotamian myth (indicated by the Yellow Nile on my map; see West for more), and is heavy on mythological and folkloric elements pulled from ancient oral poems with little regard for coherent structure. The wedding of Thetis and Peleus, Achilles’ birth and some of his childhood, the Judgement of Paris, the birth of Helen and her twin brothers along with her elopement with Paris, are presented. The recruiting of the heroes to lead the army,5 the first gathering of the fleet at Aulis, followed by the Teuthranian debacle,6 the second gathering at Aulis and the sacrifice of Iphigenia are told; then the voyage to Troy (with various adventures), the failed embassy and the start of the war. Achilles’ raids (listed in the Iliad) are recalled and a probable sexual encounter between him and Helen (arranged by Thetis and Aphrodite at his request) is included in the poem. Later, there is an episode where the army becomes despondent and wants to go home, but Achilles convinces them to stay (upstaging Agamemnon). Aeneas is introduced; Achilles’ pursuit of him leads to the capture of Chryseis and Briseis, setting the stage for the quarrel with Agamemnon that begins the Iliad. The killing of Troilus is described and Priam’s daughter Polyxena may have been introduced here. The poem ends by signaling Zeus’s plan for Achilles (to remove him from the war) and a list of Troy’s allies.

It’s easy to see from my overview (which isn’t comprehensive) why Aristotle and others criticize it; it is not so much an epic as a mishmash of episodes culled from older poems. The composer/compiler seems to have crammed in whatever he heard that related to the period prior to the start of the Iliad, with little attempt at discernment. West comments the quality of the surviving fragments is fairly high but this can hardly make up for its deficient structure. In an oral tradition where many versions of related tales existed, such a muddle is probably to be expected, and contrasts sharply with the skill of the Iliad’s composition.7

The Little Iliad, which tells the story after Achilles’ death, is similar in this regard. It begins with the awarding of Achilles’ armor and Ajax’s madness and suicide, overlapping the end of the Aethiopis, and originally included the sack of Troy, carrying the narrative through to the war’s end. Like the Cypria, it incorporates many old folkloric themes, related to a series of hoops the Greeks must jump through to take Troy. The list is long and rather absurd, made up of old independent poems (per West) and shows a distinct lack of storytelling ability. Like the Cypria, it reflects an uncritical amalgamation of oral traditions.

In contrast, the Sack of Troy appears to have been a more unified poem, likely composed not long after the Iliad became popular (subject to my caveat above). West thinks it never achieved much currency in ancient Greece, so the composer/compiler of the Little Iliad presented his own version of the sack. In addition to a great deal of gratuitous slaughter, rape, and general mayhem, the account of the sack has a decidedly tawdry feel to it, right down to Helen flashing Menelaus.8

The Nostoi, relating the tales of the Greeks’ return, is an interesting case. Per West, there is evidence it was composed in concert with the Odyssey, possibly by the same poet, or a poet who was in contact with the Odyssey poet. The major theme of the Nostoi is Agamemnon’s return, his murder by Clytemnestra (his wife) and her lover, and the subsequent vengeance taken by his son, Orestes. The coordination between the two poems is suggested by their timelines. In order for Orestes to avenge his father’s murder, he must grow to manhood. Accordingly, Menelaus’ return (with Helen) is delayed for seven years; otherwise, it would’ve fallen to Menelaus to avenge his brother.

This in turn forced a delay in Odysseus’ return because in that epic Telemachus (his son) visits Menelaus and Helen in Sparta seeking news of his father. The main parts of Odysseus’ return, which reflects the themes of a “proto-Odyssey” (the Tale of the Returning Husband and the Tale of the One-eyed Ogre) wouldn’t have needed ten years for Odysseus to get home, but because of Agamemnon’s narrative and its effect on the story of Menelaus, it became necessary to insert Odysseus’ extended stay with Calypso to make the timing work. (The year spent with Circe, where Odysseus fathers a son who will eventually cause his death, may have been in a “proto-Odyssey” as part of Odysseus’ original story.) The Calypso interlude is dealt with briefly, suggesting there was no preexisting model for it. This is the only evidence we have of coordination in the cyclic process.

The Odyssey itself is not part of the cyclic process. Like the Iliad, it is a unified, self-contained epic which (like the Iliad) makes reference to other epics, and it consciously imitates the style of the Iliad. How the style of the Cyclic poems compared to the Iliad (or the Odyssey) we can’t tell from what has been passed down about them. What is clear (despite notes of protest from some scholars) is that their reputation for being esthetically inferior is well deserved, especially the Aethiopis, Little Iliad and Sack; their plots alone reveal their substandard, deficient, even shoddy, nature – especially compared to the Iliad and Odyssey.

The Telegony is a true sequel to the Odyssey (rather than a continuation like the Aethiopis), being composed late and being more developed, compared to the Jackdaw-like structure of the Cypria and the Little Iliad. By wrapping up the life of Odysseus, it seems to be a fitting end to the Trojan War story, and it seems to me the ancients agreed because after the Telegony, I can find no evidence of a significant expansion or extension of the legend. All subsequent creative efforts are elaborations or different takes on set themes, such as carrying the story of Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Orestes to a “logical” conclusion, which I might suggest also has the hallmarks of an ancient myth, adapted to serve the Trojan War legend.9 This is evidenced by the many tragedies composed by Greek playwrights and continues even today in the popular retellings of the Trojan War stories (which, based on reviews, are often judged according to their fidelity to the legends as we currently have them).

One last point is notable about this phase: this is when the Iliad itself first became subject to revision in order to bring it more inline with the Mythopoetic tradition. Several major interpolations may have happened fairly early in this phase or they could have come after the Cyclic poems were in wide circulation, thus requiring adjustments to the Iliad. I lean to them being added near the start of the cyclic process because they are central to it. Accordingly, I’ve indicated them on my map at Atbara, and suggest they were fully integrated by the 5th cataract.

The least controversial of these interpolations is the whole of Book 10, the Doloneia, being nearly unanimously accepted. The purpose of adding Book 10 was to elevate Odysseus’ status in the Iliad, as he was destined to become the Greek’s principle hero after the death of Achilles. West dates it to the end of the 7th century or the very beginning of the 6th, based on artwork and a tendency to use “Odyssean” language.10 (Despite it being accepted as an interpolation, all translations I know of but one include it in the Iliad, with varying amounts of comment as to its origin.)

The next important interpolation is the supposed reference to the Judgement of Paris in Book 24. Opinion has been divided on whether it belongs in Homer’s Iliad or not; my opinion is that it does not (see my brief discussion in Wrestling with Proteus). As the prime cause of the war, its absence from the Iliad would seem unacceptable and have to be fixed. It could have been added at any time in the Cyclic phase, but perhaps earlier rather than later, given its importance to the Mythopoetic narrative. (I’ll have more to say about the Judgement of Paris in another essay.)

The last important likely interpolation I have not yet seen commented on in any source I have read: it is the account of the destruction of the wall around the Greek camp at the beginning of Book 12. For the sake of brevity, I’ll also address this in another essay. The importance here is that this account may have been inspired by Sennacherib’s destruction of Babylon in 689 which has led some scholars, including Martin West, to suggest the Iliad was completed after this date. However, if this account is an interpolation (as I shall argue), it would indicate the Iliad was completed before this date, as many currently believe.11

The purpose (an importance) of this account of the wall’s destruction is that it’s the first explicit mention of the sack of Troy in the Iliad; the only other explicit reference comes when Zeus is giving Hera a dressing down in Book 15. Given that the legend of the Trojan War also came to be considered the legend of the fall of Troy, absence of any explicit mention of the sack in the Iliad would be intolerable. I believe Homer avoided it for the perfectly valid reason it did not form part of the tradition he was working from (again, see Wrestling with Proteus), but when the cyclic endeavor got underway, this was a point that had to be fixed and so the interpolations to Books 12 and 15 were added. Again, because they are so crucial to the narrative, I would say they could have been added by the middle of the 7th century, and I’ve shown them as such on my roadmap, along with Book 10 and the Judgement of Paris.

This concludes my discussion of the Cyclic phase. To try to sum up, what I believe happened during it was the amalgamation of two traditions, which evolved separately and existed in parallel for a time, but became amalgamated because of 1) the nature of the war itself, and 2) the literary genius of Homer. Had the war not been such a momentous event or had Homer not been such a transformational poet, I think the traditions would have remained separate, as they did prior to Homer and as they have in other cultures. It’s a testament to Homer’s genius that the Iliad had to be incorporated into the Greek’s Mythopoetic tradition and their worldview as a whole. I’m not aware of this happening elsewhere in history with a literary work by a single individual. (If you know differently, please leave a comment to that effect!)

References for the Cyclic Phase:

As the Cyclic poems have been a major focus of Homeric scholarship for over 200 years, discussions about it are innumerable. Below is a sampling of those I’ve consulted. Martin West’s 2013 book, The Epic Cycle, must head the list and I consider other sources secondary, for the most part. They are, nonetheless, valuable to appreciate additional details and the differences of opinion found in the field.

Note: Some, especially the work of Malcolm Davies, go into extreme detail and are not easily digested by nonspecialists such as myself. However, they do make interesting points that can repay the effort of reading them.

Burgess, Jonathan. “The Non-Homeric Cypria.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), vol. 126, 1996, pp. 77–99. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/370172.

Davies, Malcolm. The Aethiopis: Neo-Neoanalysis Reanalyzed. Hellenic Studies Series 71. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2016.

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_DaviesM.The_Aethiopis.2016.

Davies, Malcolm. The Cypria. Hellenic Studies Series 83. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_DaviesM.The_Cypria.2019.

Finkelberg, Margalit. “The Cypria, the Iliad, and the Problem of Multiformity in Oral and Written Tradition.” Classical Philology, vol. 95, no. 1, 2000, pp. 1–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/270642.

Mackie, C. J. “Iliad 24 and The Judgement of Paris.” The Classical Quarterly 63, no. 1, (2013): 1–16.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/23470072.

West, Martin. “‘Iliad’ and ‘Aethiopis.’” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, 2003, pp. 1–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3556478.

West, Martin. “The Date of the ‘Iliad.’” Museum Helveticum, vol. 52, no. 4, 1995, pp. 203–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24819564.

West, Martin. The Epic Cycle: A Commentary on the Lost Troy Epics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

7. The Final Phase: The Trojan War as we know it.

This brings me to the final phase of my roadmap, where the legend became “finalized” or “fixed” into the form it’s been handed down to us. It started with the epics relating the Trojan War being assembled into something like their current order under Peisistratus of Athens, or perhaps more likely his son, during the period of 560-527. (See Strauss 2006, xiii; West 2011; and Bryce 2005, 32.) Peisistratus (or his son) did this to enhance the stature of the Panathenaic Games, and offered prizes for rhapsodes performing parts of the epics. Although it no doubt had long been the case that epics would generally be performed in parts, according to the wishes of the host (Demodocus of the Odyssey provides a clear picture of this), and may have been performed in whole at festivals prior to this (perhaps going back to the early Iron Age; see Bachvarova), it seems to be here that a “unified” Trojan War legend was first performed, and the idea of breaking the individual epics into manageable “books” for rhapsodes to perform in order over the length of the festival was instituted.12 How this division at the Panathenaic Games compares to the books we have today is unknowable, but given the exigencies of performance and the natural breaks that occur in the Iliad and Odyssey, it likely wasn’t that much different.

After this period (and probably during it as well), the epics continued to be performed and (per West) were distributed increasingly as books, each book being more tractable to copy than entire epics. Mentions of the Trojan War appear in Herodotus and Thucydides (484-400). I At the same time, Greek playwrights took up Trojan War themes with gusto, producing numerous plays about various episodes. So did Greek lyric poets, especially Pindar (518-438). It was another period of great creative outpouring related to the Trojan War and, as this is the period from which the bulk of the surviving works date, we get much of our knowledge of the legend from it.

According to Aristotle, the Trojan War epics were organized into a formal, comprehensive cycle between 350-320. He says this was done by one Phayllos, about whom we know nothing else. Phayllos wrote a protocol defining it and wrote a prose summary (periochai) for each epic. (West 2013, 23-25.)

Around 200, scholars in Alexandria labored to create a “definitive” version of the legend, particularly purging the Iliad of what they considered to be “extraneous” or “wild” lines that had been inserted into the epic over the previous centuries. The activities of these scholars have been subject to much debate, but their efforts resulted in what is called the Alexandrian Vulgate.13 At this time, copies of the Cyclic poems seem to be getting rarer, and the poems were probably better known from prose summaries and digests (West 2013, 47). (The Theban War poems appear to have long since faded from view and were known only from summaries and fragments.)

The Roman poet Virgil wrote the Aeneid between the years 29 to 19, inspired by the Iliad and especially the Odyssey, but drawing in some of the cyclic material as well, particularly the legend of Penthesilea, whom he presents as the warrior queen Camilla (whose character was also influenced by the myth of the Greek heroine Atalanta).

In the 2nd century AD, Pausanias mentions he’s read some of the Cyclic poems, but implies this is uncommon, copies of the poems themselves being quite rare; it appears he had assembled a personal library of ancient texts.14 Sometime in this century, Proclus and Apollodorus were active, creating their summaries of the Cyclic poems from digests that were “current no later than the Hellenistic period,” according to West (2013, 14). Proclus’ famous Chrestomathy supplies us with most of our knowledge of the Cyclic poems.15 The original document is lost and we know it primarily from authors writing in the 10th century AD. Apollodorus covers the same ground in his Bibliotheca, but provides additional details not found in Proclus.

West remarks that after 200 AD, “direct knowledge of the Cyclic poems really seems to fade out” (West 2013, 50). When the Greek poet Quintus of Smyrna provided his own take on the Trojan War in his Posthomerica, writing in the 3rd or 4th century AD, it’s doubtful he had access to the poems’ texts but told the story as he knew it from earlier synopses, descriptions and commentaries. Although a creative retelling of his own, it appears to preserve many elements of the original stories otherwise lost and is valuable on that basis.

Retellings continued, appearing in the works of Chaucer (1342/43-1400 AD) and other authors from slightly later,16 in Shakespeare and (as previously mentioned) in stories by present-day authors. I expect this practice will continue and the Trojan War will be with us for a long time to come; its “delta” will continue to spread, even as the “river” Homer engineered remains largely unchanged.

This, at least, is what I have so far deduced. As noted, it remains a work in progress, and (as noted) I will elaborate on some of the points I’ve suggested here in greater detail in future essays. What do you think? Am I barking up the wrong tree? Climbing out on an limb of said tree? Climbing out on said tree limb over thin ice? Share your thoughts, if you have them.

And as always, boundless thanks to the sturdy souls who have made it this far. My appreciation for the time you’ve spent here is beyond the utmost power of language to express.

Further Reading

The following are some additional sources I also found useful in creating my roadmap, or generally for filling in some of the background. As always, it’s merely a potential starting point for those interested; better and more comprehensive lists are available. For convenience (I hope), I’ve list books first and articles next.

Books:

Bryce, Trevor. The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bryce, Trevor. The Trojans and their Neighbours. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2006.

Homer. The Odyssey (translated by Emily Wilson). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997.

Mayor, Adrienne. The Amazons. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Nagy, Gregory. Homeric Questions.

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homeric_Questions. 1996

Porter, Andrew. Homer and the Trojan Cycle: Recovering the Oral Traditional Relationship. Society of Biblical Literature, 2022.

Slatkin, Laura. The Power of Thetis: Allusion and Interpretation in the Iliad. Berkeley and Los Angeles; University of California Press. 1991.

West, Martin. Indo-European Poetry and Myth. OUP Oxford, 2007. pp. 137.

Articles:

Bryce, Trevor. “Madduwatta and Hittite Policy in Western Anatolia.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, vol. 35, no. 1, 1986, pp. 1–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4435946.

Jablonka, Peter. “Troy in regional and international context”. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). Oxford University Press, 2011.

Kelly, Adrian. “Homer and History: Iliad 9.381-4.” Mnemosyne 59, no. 3, 2006, pp. 321–33. http://doi:10.1163/156852506778132400.

Lambrou, Ioannis. Homer and the Trojan Cycle: dialogue and challenge. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Greek and Latin, University College London, 2015.

Leinieks, Valdis. “The ‘Iliad’ and The Trojan Cycle.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 52, no. 6, 1975, pp. 62–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43933461.

Nagy, Gregory. “Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology IV, Reconstructing Hēraklēs backward in time.” Classical Inquiries. Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, 2019.08.15. http://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively-about-greek-mythology-iv-reconstructing-herakles-backward-in-time/.

Nagy, Gregory. “Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology XII, Hēraklēs at his station in Mycenaean Tiryns.” Classical Inquiries. Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, 2019.10.11. http://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively-about-greek-mythology-xv/.

Ross, Shawn. “Homer as History: Greeks and Others in a Dark Age.” Reading Homer : film and text / edited by Kostas Myrsiades, 2009, pp. 21–57. www.academia.edu/19667270/Homer_as_History_Greeks_and_Others_in_a_Dark_Age.

Sherratt, E. S. “‘Reading the Texts’: Archaeology and the Homeric Question.” Antiquity 64, no. 245, 1990, pp. 807–24. http://doi:10.1017/S0003598X00078893.

Slatkin, Laura. “The Wrath of Thetis.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), vol. 116, 1986, pp. 1–24. http://doi.org/10.2307/283907.

Starr, Chester G. “Peisistratus”. Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Peisistratus.

West, Martin. “The Homeric Question Today.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 155, no. 4, 2011, pp. 383–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23208780.

West, Martin. “The Invention of Homer.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2, 1999, pp. 364–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/639863. West, Martin. “Trojan Cycle” in Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd. ed. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 1999.

West, Martin. 1975. Immortal Helen. London.

Wiener, Malcolm H. “Homer and History: Old Questions, New Evidence”, EPOS: Reconsidering Greek Epic and Aegean Bronze Age Archaeology, Proceedings of the 11th International Aegean Conference, Los Angeles, UCLA-The J. Paul Getty Villa (20–23 April 2006), Aegaeum 28, 2007, pp. 3–33.

Xian, Ruobing. “Recent Homeric Research.” Museum Sinicum, 2018.

Footnotes

I recall a suggestion that the Cypria and Little Iliad may have originally attempted to tell the full story of the Trojan War, making them standalone works that were cut down to bracket the Iliad and Aethiopis, but West does not support this and specific references elude me. If anyone can identify sources for this, please leave a comment!

If I recall correctly, the Blue Nile contributed more water to the Nile than the White. Something similar might be said of the Mythopoetic tradition and the Iliad. It makes Homer’s genius all the more remarkable that his single work came to eventually overshadow, and indeed outlast all the countless contributors to the Mythopoetic tradition. Only the poet of the Odyssey, who occupies a sort of middle ground between the Iliad and the Mythopoetic tales, stands with him.

This is a subject of debate. I’ll address it elsewhere.

To recap this incident: Ajax (the Greater) and Odysseus were the major heroes who each played a leading role in the battle over Achilles’ body. When it came to awarding Achilles’ armor after his funeral – a signal honor – Odysseus was selected over Ajax. Ajax succumbed to a fit of madness the following night and attacked the Greek army’s flocks and herds. Overcome with mortification when he realized what he’d done, he committed suicide. Given Ajax’s antiquity, it seems plausible that this tale is a very old one which predates either Achilles’ or Odysseus’ incorporation into the legend, but reflects events from the first stages of the Trojan War in the 15th century.

Including Odysseus feigning madness but not the tale of Achilles being hidden among the women of Skyros. Skyros is an island east of Lesbos the Greeks visited on their way to Troy.

Achilles fathering a son with Princess Deidamia of Skyros on the way back from Teuthrania is mentioned.

Herodotus knew a version of the Cypria that differs in regard to Paris and Helen’s voyage back to Troy, suggesting that multiple versions of the poem may have been in circulation during his time.

One ancient commentator goes so far as to describe Helen’s breasts as her “apples.” The degree to which he was being crass or ironic (“apples” of discord?) cannot be determined. Apples were thought to have aphrodisiac properties in ancient times.

To elaborate on this briefly, the basic tale (setting aside the “Curse of the House of Atrius”) is that a king offends against a deity, who demands the sacrifice of an offspring in compensation. The child’s mother, consumed by grief, plots revenge on her husband and carries it out with the help of a lover. The couple’s son thereby becomes obligated to avenge his father’s murder by killing his mother, earning eternal damnation (and persecution) for matricide, which is finally resolved. Similar themes are found throughout Indo-European myth in various forms (including the famous story of Oedipus) and have even made their way into the Old Testament. I therefore think it’s possible, without denying Greek playwrights considerable artistic license, that this story (like so much else in the Trojan War legend) has very ancient roots indeed.

Why Odysseus was selected for this role, rather then Diomedes, is an interesting question I plan to consider in the future. As Ajax’s suicide was already well established by the first quarter of the 7th century, based on depictions of it in art (West 2013, 162), he would not have been available to take over Achilles’ role as the main Greek hero.

For reference, Robin Lane Fox says 740-700, and considers anything later than 680 insupportable. Richard Janko argues for a similar date or even a bit earlier. Barry Powell argues for 800; the earliest date among Homeric scholars. Barry Strauss says the 700s and Trevor Bryce agrees, placing it later in the century, as do recent translators. Martin West argued for a later date, 680-640, based on instances in the Iliad such as the destruction of the Greek’s wall and several others that I consider suspect. Following Fox, Janko, Bryce, Strauss and the translators, I accept 740-700 as a best estimate, erring toward Homer starting his epic a decade or so after 740 and completing it around 700 or slightly later.

How the epics were assembled and by what authorities is a matter of debate. It need not have been entirely, or even mostly, through reference to written texts; the evidence is mixed. I’ll review this debate later in another essay.

After the Arthurian Vulgate Cycle (or Lancelot-Grail Cycle) and the so-called “Post-Vulgate Cycle” composed in the early to mid-13th century AD and which, when taken together, purport to relate the tale of King Arthur as a historical chronicle, combining the various parts of the Arthurian legend into a coherent whole. I mention this because it has a bearing on understanding the Trojan War legend’s development; the subject of a another essay I have in work.

According to West, Pausanias, a Greek geographer who traveled widely, is the only author of this period to quote fragments of the Cyclic poems who says he’s actually read the poems; few of his contemporaries had ever seen them (West 2013, 49.)

Some ancient sources place Proclus in the 5th century AD but West convincingly argues they are confusing him with Proclus of Lycia, a well-known 5th century Neoplatonist (West 2013, 7-8).

Christine de Pizan (1405 AD) and John Lydgate (1420 AD).