Helen of Troy is arguably our most enduring cultural icon. She is also one of the most polarizing and least understood, with an unsurpassed ability to create controversy. Her nature, however, remains elusive. This essay examines Helen’s history in literature within the context of Indo-European religion and Bronze Age history and by applying a multidisciplinary approach, suggests there may be parallel traditions about Helen which could account for the view she epitomizes the kalon kakon (beautiful evil). The essay’s purpose is less to present conclusions than to stimulate discussion of different ways to explore Helen’s ambiguous character.

I am presenting this essay in four installments. This first installment introduces Helen’s controversial character and explores her nature as a goddess of ancient origin, the significance of her twin brothers, Kastōr and Poludeukēs (themselves ancient deities), what is behind her propensity for martial strife and being abducted, and her (perhaps unexpected) connection with Cassandra, the beautiful, cursed Trojan seer.

References are indicated by brackets [1] but not linked (due to the current limitations of Substack when importing from MS Word files). Explanatory footnotes are linked. All works cited are listed at the end of the final installment.

Keywords: Helen of Troy, Helen of Sparta, Helen’s eidōlon, Helen in the Iliad, Helen in the Cyclic poems, the Sun Maiden, Bronze Age Anatolian Conflicts, Alaksandu of Wilusa.

Acknowledgements: I am deeply indebted to Cynthia Gralla of Royal Roads University for her kind assistance and support in the creation of this work, including help with research, excellent editorial suggestions and many insightful comments. I also received much-needed help and encouragement from Eric Luttrell of Texas A&M, which was indispensable to formulating my arguments and correcting my unfounded suppositions. They have saved me from many embarrassing errors. Those that remain are solely my own.

Part 1: Introduction

Helen of Troy, Helen of Sparta, or just Helen – call her what you will – is one of the most famous and enduring icons in Western tradition, and perhaps the most polarizing. For over two and a half thousand years, people have expressed their opinions about her, opinions that have rarely been mild. She has been worshipped as a goddess and reviled as a whore, labeled an agent of destruction and even blamed for the Bronze Age collapse.1 Ruby Blondell describes her as “notoriously complex and ambiguous” and says that in her epic form, she “embodies the kalon kakon – the irreducible complex of beauty and evil” – while the late Martin West said the Iliadic Helen “behaves perfectly in every situation” and comes across as the “most marvelous, sincere, sweet-natured woman in ancient literature.”[1] Her ability to excite passions and create controversy has remained undiminished since she first appeared in the Iliad.

But what might lie behind Helen and her “notoriously complex and ambiguous” character? Is she simply an icon? The question takes on additional poignancy when we consider the tradition that Helen did not go to Troy at all but spent the war in Egypt, while the Trojan price, Paris, took a phantom-double of her – an eidōlon – back home with him. It is not hard to see the irony of men fighting a devastating war over what, in Gregory Nagy’s words, was merely a “figment of their imagination.”2

The foregoing suggests that Helen’s power derives in part, even large part, from her unreality. She is either a phantom or a goddess; neither are truly accessible, despite Helen’s eidōlon in Troy acting as the actual Helen could, even being capable of having sex. This led Donna Zuckerberg to ask: “In what sense was the eidōlon less ‘real’ than Helen herself?” In turn, I ask: to what extent is an eidōlon eclipsing our view of Helen herself?

The lines are blurred from the very beginning of Helen’s literary history. In his article “Helen of Sparta and her very own Eidolon,” Nagy points out the contradictions between the Iliadic Helen and the Helen in the lyric tradition first attested in Stesichorus: “the lyric version corrects the epic version by unsinging, as it were, the epic appearance of Helen as a mortal woman at Troy and by resinging her lyric reality as an immortal goddess at Sparta.”[2] He continues his point in his article “Just look at all the shining bronze here, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” saying of the Odyssey: “…we can see that she has finally left behind her temporary human existence at Troy and has returned to her permanent divine existence at Sparta.”[3]

Thus, the Helen in the Iliad seems quite different from the Helen of the Odyssey and this causes difficulties. Nagy states this explicitly: “[H]ow do we square the idea of Helen as goddess of Sparta with the idea of Helen of Troy as we see her come to life in the Homeric Iliad?”[4]

Nagy proposes an elegant solution to this old problem; his admirably concise discussion repays a close reading. This essay takes a different approach — less to propose a solution than to offer food for thought.

Helen in Literature: Goddess or not?

To begin, it will be useful to review Helen’s nature as a goddess, which is not entirely straightforward. Helen is popularly portrayed as the child of Leda, queen of Sparta and wife of Tyndareus, and Zeus, who appeared to Leda as a swan. This story is best known from Euripides’s Helen, but Nagy mentions other traditions, some from Sparta, in which Leda is Helen’s birth mother.3 This origin makes Helen a demi-god and mortal by the “genetic rules” of Greek myth, which is how she is presented throughout the play.4

Prior to Euripides, however, the Cypria noted Helen as the daughter of Nemesis, who was assaulted by Zeus while both were in the form of geese, possibly explaining Zeus’ swan form in the Leda episode. Helen is thus fully a goddess in this tradition, which includes her portrayal in the Odyssey.5

Outside the Cypria and Odyssey, Helen’s nature is less clear; in the Cyclic poems, her supernatural abilities are limited to imitating the voices of the wives of the Greek heroes hidden within the Trojan Horse, and the Lesbian poets, in their surviving work, make no reference to Helen having a divine or even semi-divine nature.[5] So the record is mixed: depending on the tradition, Helen was either a goddess or semi-divine but mortal.

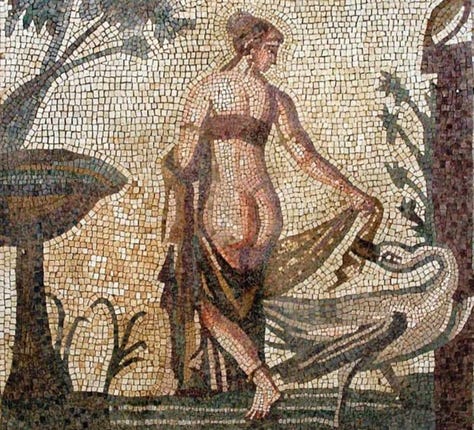

The existence of these different traditions may seem a bit odd since it is widely accepted that Helen was worshipped as a goddess in Greece, particularly in Sparta/ Lacedaemon as far back as the Bronze Age (likely accounting for Helen being Spartan in the legend). But this is not the full extent, because Helen (or her prototype, if one prefers) was not simply a goddess in Greece, but one of the greatest antiquity. Her name associates her with the sun; Martin West proposed that Helena derives from the reconstructed term *Swelenā, “mistress of sunlight” – that is, the Sun Maiden or Daughter of the Sun – one of the five most securely reconstructed proto-Indo-European deities, whose worship extended throughout Indo-European cultures and who lives on in our traditions of Easter eggs, Christmas trees and May poles.[6]

One of the more intriguing (though perhaps obscure) connections of Helen to the Sun Maiden appears in her wooing by her many suitors. West observed that suitors competing in athletic contests and offering lavish gifts for her hand has little in common with Greek marriage practices of the time.[7] Seemingly more outré is the involvement of a horse sacrifice. The Archaic-age Greeks rarely if ever practiced horse sacrifice, but their ancient ancestors did, along with holding contests to choose the husband for a coveted bride (as recounted in many Indo-European myths).6 The wooing of Helen therefore has echoes of early Indo-European practices related to the Sun Maiden and her association with horses via her companions, the Divine Twins, another of the securely reconstructed proto-Indo-European deities.

Of particular interest is the appearance of the Sun Maiden in conjunction with the Storm God on Bronze Age cylinder seals from western Anatolia as a multi-functional goddess, combining a fertility/sexual aspect with a martial aspect.[8] These seals show, via her intimate association with the principle god, that the Sun Maiden was a major deity whose worship extended over a wide area during the latter half of the second millennium BC.7

The Helen of Greek myth has all the Sun Maiden’s major characteristics.8 The two most pertinent to this discussion are 1) her connection with the aforementioned Divine Twins, and 2) her propensity for strife in her relationships, including abduction.

The Divine Twins are represented in Greek myth by Helen’s brothers, Kastōr and Poludeukēs, most often known by their Latin names, Castor and Pollux, and collectively as the Dioskouroi (latinized Dioscuri), which is Greek for “sons of Zeus.” However, their paternity is conflicted. In the pseudo-Hesiodic Catalog of Women they are both sons of Zeus, but in the Odyssey (11.298–304) they are the sons of Tyndareus; in later tradition (first found in Pindar, Nemean 10), Pollux is the son of Zeus, who appeared in the guise of Leda’s husband, while Castor was fathered by Tyndareus, who impregnated Leda the same night. Accordingly, the Dioscuri are alternatively both immortal, both mortal, or Pollux immortal and Castor mortal. (See Nagy on Pollux’s immortality.[9]) The upshot is that the Twins’ divine status resembles that of Helen herself: sometimes divine, sometimes mortal, sometimes collectively “semi-divine.” And, like Helen, they are proto-Indo-European deities, and in Greek myth they are subject to the same confusion.

Before I address possible reasons for this confusion, it is worth asking what the Dioscuri are doing in the Trojan War myth at all since they play no meaningful role in it. A simple answer is that Helen is the Sun Maiden and where the Sun Maiden is, the Divine Twins must also be. So the Dioscuri were brought into the legend and, when it became expedient, were taken out.9 The manner in which they were taken out is also characteristic of ancient Indo-European myth. The Twins wished to marry the daughters of Leukippos, who were already betrothed to another set of twins, the Dioscuri’s cousins.10 In the dispute that followed, Castor was killed, and in the tradition where only Pollux is the son of Zeus, he shares his immortality with his deceased brother.11 This story, which would seem to have no place in the Trojan War legend, also brings in the common Indo-European motifs of bride stealing, cattle raiding and twin sacrifice.[10]

From here, we can discuss the second, more important, aspect of the Sun Maiden: her tendency to have marital difficulties and to be abducted. Four abductions appear in the Trojan War legend, all involving the Sun Maiden in some form. I’ve just discussed the abduction of the daughters of Leukippos by the Dioscuri. Another is Helen’s abduction as a child by Theseus, in which the Dioscuri are involved, but as rescuers.12 A third involves Agamemnon taking Cassandra back to Greece as his slave after the fall of Troy. While part of Smoot’s evidence for this assertion is weak (claiming Cassandra is the most beautiful of Trojan women), that the Trojans worshipped the Sun Maiden gives credence to the existence of a Trojan Sun Maiden.13 As a beautiful seer who was cursed by Apollo for refusing him (Leukippos’ daughters are linked to him in a similar way), Cassandra certainly fits the bill.14

The last abduction is, of course, Helen by Paris, although this might better be called an elopement, since seduction appears to have been involved and who seduced whom remains an open question. This abduction is the only one meaningful to the story, and indeed, it is central, being the war’s casus belli. But the presence of four abductions of a Sun Maiden figure, three of which are essentially irrelevant, plus the confusion over Helen’s divine status and that of the Dioscuri, should give us pause. Let’s start by examining whether the Iliadic Helen is mortal or not.

Nagy contends she is not – that she is portrayed as a goddess in the Iliad, but in a special way. His argument has weight, but I see reasons to question it. One of his key points is that Helen is called Dios ekgegauia “born of Zeus” in the Iliad and the Odyssey, and also Dios thugatēr “daughter of Zeus” in the Odyssey. As he observes, this latter epithet is only applied to goddesses in both poems.[11]

Before we proceed with this line of reasoning, it is important to note that the Odyssey should be divorced from the Iliad. The preponderance of evidence indicates the Iliad was composed by an Ionian Greek poet from western Anatolia in the latter half of the eighth century. The Odyssey, on the other hand, appears to have been composed a century or more later by a poet from mainland Greece.15 Thus the two poems were composed at different times, in different places, and for different reasons. Although they are both considered “Homeric,” they are dissimilar and follow different traditions. The Odyssey is a nostoi (return) and is related more closely to the Cyclic poems than to the Iliad. To use them both is to mix apples and oranges, as it were.

Therefore, restricting my assessment to the Iliad alone, several points are noteworthy. First, Helen is portrayed as mortal in the Iliad with no hint of divine nature except in one scene (3.399–420) where she angrily confronts Aphrodite and tells her that if she is so enamored of Paris, she should forsake Olympus and take up with him until he makes her either his wife or his slave.16 Suggesting to an Olympian goddess that she should become enslaved to a mortal man is not something one would expect Helen to say if she were mortal, and the exchange, including Aphrodite’s tart rejoinder, sounds rather like a spat between two goddesses who know one another pretty well.

In addition, Helen recognizes Aphrodite in this scene despite Aphrodite having taken the form of an aged servant. This is not a strong argument for any special ability of Helen’s, though, as it is not clear if Aphrodite meant to fool Helen or just others, since she makes no effort to hide her identity.

Perhaps more importantly, in all the instances of Helen’s name in the Iliad, her relationship to Zeus is mentioned only three times, all in Book 3: 199, 418 and 426; the last two occur during her confrontation with Aphrodite. At 199 and 418, Helen is called “born of Zeus”; 426 is the only line where she is called “daughter of Zeus.” However, this line is constructed a bit oddly: Aphrodite has just placed a stool for Helen, who sits on it and is about to berate Paris; the line reads: “There Helen took her seat, daughter of Zeus who wields the aegis.”[12] Helen is sitting next a goddess regularly called “daughter of Zeus” – how certain is it “daughter of Zeus” refers to Helen here?17

Further, the epithets “daughter of Zeus” and “born of Zeus” are not quite the same; “daughter of Zeus” is the exclusive one. If Helen is a goddess in the Iliad, why is that epithet applied to her only once (if even then), while “born of Zeus” is applied to her only twice? Calling Helen “born of Zeus” twice does not seem like good evidence that she is considered divine, in view of her depiction in the rest of the epic.18

Finally, the Dioscuri also appear to both be mortal in the Iliad, as they both appear to be dead. Nagy offers another explanation, but the wording in the Iliad seems to point to the simpler interpretation. If Helen is a goddess, why depict her brothers as mortal? The alternative feels too elaborate.

In the end, the best evidence for Helen being a goddess in the Iliad may be her spat with Aphrodite, but even this might be qualified by observing that Diomedes attacks and actually manages to wound two deities during his aristeia, one of them the war god himself. So mortals are not barred in the Iliad from directly confronting their gods. The safest conclusion would be that the Iliad considers Helen to be a mortal and is tepid about her being even semi-divine.

In the context of the Iliad, this is not surprising. Homer is noted for downplaying, marginalizing, or even ignoring mythological elements.19 C. J. Mackie refers to “Homer’s rather austere way of keeping some narratives to the margins of the Iliad… Some traditional narratives are kept out of the poem, only to be alluded to in the barest of ways.”[13] So while Homer must have been aware of Helen’s connection to the Sun Maiden, since he includes a brief mention of her brothers (perhaps to explain their absence from the epic?), he did not seem to want to deal with the question of her possibly divine nature (or theirs). Since his audiences must have known the other tradition, he had to throw in a bare acknowledgment, which he did, but then moved on without further reference to it.

Thus, it appears the Iliad does consider Helen to be mortal while giving a nod to the tradition of a divine Helen. This brings me back to my previous statement that having two such traditions may seem a bit odd. In saying that, I should point out that nothing is inherently strange about this. In our own society, we have history, historical fiction and fantasy, and when they deal with the same subject, we see no conflict. So, for example, we feel no need to reconcile Samuel Elliot Morrison’s histories with the novels of Herman Wouk or Marvel’s Captain America comics, even though they all deal with WWII. The ancient Greeks’ literary landscape was no less diverse, and they had no less of a sophisticated appreciation of it than we do.

But some differences do appear with the example I just used: WWII is a historical event, subject to being treated in different ways. If the Trojan War is merely a fable, why invent multiple traditions including Helen’s divinity or lack thereof? The historical reality of the Trojan War has been much debated for a long time, but in recent decades the needle has swung toward it being a historical event. As a historical event, the door is open for various traditions about it.20

The Trojan War being historical (in some form) brings up another issue: what is a proto-Indo-European goddess doing in the story, especially as the cause of the war? The Sun Maiden predates any possible Trojan War by thousands of years, yet the traditions associated with her are crucial to the story we have of the war itself. If the war indeed has a historical basis, why should this be the case?

It is not that the Iliad is a historical document; obviously, it is not lacking in mythical and legendary characters (indeed, quite the opposite).21 Again, there should be no surprise here: the tale of a great war from a heroic age long past requires outstanding heroes, and myth and legend can supply them. However, this does not explain the presence of Helen or why she has a dual nature. If the war happened and stories of it were preserved, it is reasonable to believe its cause would be preserved as well.22

But was Helen actually the cause if the war? We should examine the case for her guilt or innocence next.

This concludes Part 1.

References

[1] West, “Immortal Helen.”

[2] Nagy, “Helen of Sparta.”

[3] Nagy, “Just to look at all the shining bronze,” referring to Odyssey 4.227.

[4] Nagy, “Helen of Sparta.”

[5] Blondell, “Refractions of Homer's Helen,” n.21.

[6] See Mallory and Adams (2006), and West (1975 and 2007). Smoot also presents an overview of Helen’s etymology. (Smoot, “Helenos.”)

[7] West (2011).

[8] Woudhuizen (2018).

[9] Nagy, “Helen of Sparta.”

[10] Jackson (2002).

[11] Nagy, “Helen of Sparta.”

[12] Caroline Alexander’s translation. (The Iliad, 2015.)

[13] Mackie, “‘Iliad’.”

Footnotes

The idea that the late Bronze Age was a “heroic age” that was brought to an end by the Trojan War appears in Hesiod (Works and Days), along with the Theban war – a tradition that was relatively short-lived. The Cyclic poems (the six lost poems about the Trojan War and its aftermath summarized by Proclus) then provided details. Helen was the cause of the Trojan War, and thus blamed for it. The idea of a “heroic age” is also suggested in the Iliad, but in a much more muted form than in Hesiod or the Cyclic poems, and Helen’s culpability is denied.

Euripides included Helen’s eidōlon in his play Helen, saying it was created by Hera out of spite for losing the Judgement of Paris, so Helen was never Paris’s wife; instead, Helen was transported by Hermes to Egypt to preserve the sanctity of her marriage to Menelaus. Euripides thus used the tradition of Helen’s eidōlon to absolve her of blame.

Nagy’s reference is a Spartan song found in Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (line 1314). The pseudo-Hesiodic Catalogue of Women also identities Leda as Helen’s mother, but is unclear if this means Helen’s birthmother or her adoptive mother. In view of the Cypria, the latter may seem more likely. Support for an ongoing tradition of Helen being the daughter of Nemesis is found in the following quote: “τὴν Ἑλένην Ἀδράστειαν ἐπιστάμενος προσκυνεῖ, ὁ δὲ Λακεδαιμόνιος Ἀγαμέμνονα Δία καὶ Φυλονόην τὴν Τυνδάρεω θυγατέρα.” “He worships Helen Adrastea, while the Lacedaemonian worships Agamemnon Zeus and Philonoe, the daughter of Tyndareus.” Adrastea is another name for Nemesis. (Smoot, “Helenos”; author’s translation.)

See Nagy, “Helen of Sparta,” for more on the “genetic rules” of Greek myth.

On the question of Helen’s eidōlon, the Odyssey is notably vague. The Odyssey poet evidently did not want to commit to a narrative. See Smoot, “Did the Helen of the Homeric Odyssey Ever Go to Troy?”, for more discussion.

The Lefkandi burial on Euboea, dated to just after 1,000, contains the bodies of sacrificed horses. Evidence of late Middle Helladic horse burial has also been found and may be an exceptional event. See Alexander (2009), p.195-196 and p.266-267, for a brief description and references on these finds.

NB: I do not endorse the description, as it reflects dated views on the interpretation of grave finds. What is remarkable about this burial is the “hero” of Lefkandi is in the presence of a woman adorned in gold with what appears to be a short sword at hand (often misidentified as a “knife”). Alexander (2009) states: “Buried with the ‘hero’ were four horses and a woman richly adorned in gold, who had possibly been sacrificed, along with personal effects that included a sword, a razor, and an iron spearhead.”

This website: http://lefkandi.classics.ox.ac.uk/Toumba.html, describes a similar grave: "In the central room two burial shafts were found: one contained the cremated body of a man buried with his weapons and an inhumed woman with remarkable jewelry; the other contained the remains of four horses.”

These burials are reminiscent of an Etruscan grave of a person buried with weapons and other goods indicating high status, and cremated companion. It was initially identified it as the grave of an Etruscan "warrior prince" and his (possibly sacrificed) female companion or wife, but DNA analysis of the remains revealed it was a woman buried with her weapons and the cremated remains of a man.

The horses at Lefkandi are buried next to the richly adorned woman, thus seeming to be more strongly connected with her than the cremated male. Further, all these burials are similar the grave of high-statue women warriors (“Amazons) of the central Asian steppes.

Such misidentifications (based primarily on grave goods) are unfortunately common, and we should question the meaning of the bodies in the Lefkandi tomb, especially in light of the Etruscan tomb findings. (Adrienne Mayor, Stanford; personal communication.)

All these burials speak to the persistence of ancient Indo-European practices (including the exalted status of female warriors) even in areas far removed from their place of origin. Care should therefore be exercised in making assumptions about the attitudes towards woman on ancient Indo-European societies, including those about Helen.

As before, all dates are BC and approximate unless indicated.

See West (1975), for a concise and illuminating discussion of Helen as the Sun Maiden. Nagy states Helen was worshipped in Sparta as the dawn goddess. (Nagy, “Just to look at all the shining bronze”). For more detail on Helen’s worship in Greece, see Bettany Hughes (2005). For a rare dissenting view, see Lowell Edmunds (2016)

West suggests they had to be removed because if they were alive, it would present the problem of two sets of brothers trying to recover her when she eloped with Paris. (West 2013.)

Smoot states that Leukippos is an epithet of Dawn. The two young women’s names are Phoibe (or Phoebe) and Hilaeira, connecting them with the sun. (Smoot, “Helenos.”)

In Greek myth, the Dioscuri have quite the career, being attested as both Argonauts and participants in the Caledonian boar hunt. Both these events took place (in mythic time) a generation or two before the birth of Helen and the Trojan War. Although this chronological discrepancy has exercised authors, ancient and modern, there is nothing very surprising about it: as Indo-European gods of great antiquity, the Dioscuri can be expected to find their way into many legends, without regard for time or place. Thus, they may have been included among the Argonauts, in the Caledonian boar hunt, and the stories of Leukippos’ daughters and Helen’s childhood independently and for different reasons. Only when these myths began to intermingle, did people begin to feel the need to rationalize the discrepancies. See Kapach (2023) for a discussion of this topic.

Helen is the third goddess Theseus adducted or tried to, as Martin West identifies Ariadne as an ancient Minoan goddess who later came to be seen as mortal. The Theseus/Helen episode brings in, if only peripherally, the motif of the “disappearing” goddess, most familiar from the Persephone myth. Here again we have an ancient Indo-European motif being “smuggled” into the story.

Cassandra is said to be the most beautiful of Priam’s daughters in the Iliad, but this is mentioned only once, and Laodike, another of Priam’s daughters, is given the same title, undermining the notion that Cassandra is unique in this regard.

According to the Cypria, Leukippos’ daughters are either actually the daughters of Apollo or the object of his affection. (Smoot, “Helenos.”)

I am, for the most part, following the analysis of Martin West here, supplemented by my own experience, research and analysis. This result is to an extent controversial, but those arguments must be made elsewhere.

Mitchell, in his 2011 translation of the Iliad, translates “slave” here as “whore,” which is even worse.

Nagy leaves this line out of his list of places where Helen is referred to as Dios ekgegauia or Dios thugatēr in both the Iliad and the Odyssey.

In the Iliad, Sarpedon (5:635) and Telamon (7:234) are referred to as “born of Zeus,” which is accurate, but neither are immortal. Thus “born of Zeus” might be a sign of having a divine parent but does not imply that Helen is an immortal goddess. Nagy addresses this by suggesting that Helen’s divine nature is occluded in Troy (“out of sight”), but again, while an interesting solution, it feels somewhat complicated. Also, Helen shows no awareness of being Zeus’ daughter and Zeus ignores her completely, showing no concern for her welfare, unlike his feelings for Sarpedon, further arguing against Helen having a divine nature in the Iliad. (Mitchell’s 2011 translation of the Iliad, note on p.422.)

As usual, I am using “Homer” to refer specifically to the Iliad poet, as distinct from the Odyssey poet.

See my essay Wrestling with Proteus for a discussion of the Trojan War’s historicity.

This is also not the same as saying the Iliad lacks any historical basis. Alexander/Paris is attested as a historical figure: he is King Alaksandu of Wilusa (Troy) who concluded a treaty with the Hittite king, Muwattalli II, in 1280.

That the Mycenaeans lacked any written history we have recovered does not mean they lacked history. They certainly had history and retained it, just as all other civilization in the Bronze Age Near East did. Latacz (2004) presents a detailed discussion, along with a convincing argument for the Trojan War story having a Mycenaean origin. Details of a historical war worth remembering, such as the cause of the war, would then have been available to Homer and his predecessors.