In this second installment of my essay, I give an overview of the historical data that may relate to a historical Trojan War, focusing on conflicts in both western Anatolia and Mycenean Greece, with particular emphasis on evidence from Hittite documents. I also touch on the relationship between Thebes and Mycenae during the late Bronze Age, and how it might relate to the conflicts in western Anatolia.

References are indicated by brackets [1] but not linked (due to the current limitations of Substack when importing from MS Word files). Explanatory footnotes are linked. All works cited are listed at the end of the final installment.

Acknowledgements: I am indebted to Prof. Eric Luttrell for his observation (below) which inspired the title of my essay and my approach, generally, and to Dr. Cynthia Gralla for her encouragement, invaluable feedback and editorial assistance.

Keywords: the Trojan War, the Iliad, the Homeric poems, the Cyclic poems, Homer, the Age of Heroes, Late Bronze Age conflicts in Anatolia, Mycenaean activities in Anatolia.

Part 2. The endeavor to “get a clue”

“The [Iliad’s] oral history, authorship, and evolution will remain inevitably protean. That doesn’t mean we can’t trace the outlines of certain elements across time and poetic iteration. We just have to be careful what inferences we add.”

Eric Luttrell, Texas A&M University (personal communication).

I shall try to abide by his caveat.

The logical place to start our match is the historical record. As in the literary realm, there are different schools of thought among historians who accept the historicity of the Trojan War. As alluded to previously, some favor the explanation that it was a minor conflict that was inflated by poetic tradition in the same manner as the Song of Roland and the Nibelungenlied. Caroline Alexander in her 2009 book, The War that Killed Achilles, characterized it as a war that “established no boundaries, won no territory, and furthered no cause.”[1] Barry Strauss, in his 2006 book, The Trojan War: A New History, analyses it as a long, drawn-out “dirty war”; what would be termed a low-intensity, asymmetric conflict in modern military parlance.

Other historians, observing the pattern of recurring conflict in western Anatolia from the mid-15th century into the 13th century, some involving Wilusa (Troy) and Ahhiyawa (Greece), suggest poets “telescoped” these conflicts into a single narrative at a late date.1 According to this theory, the manifold creators (or inheritors) of the Trojan War tradition, composing in the early Iron Age, merged these events while bringing in elements from the era of the Bronze Age collapse, setting the stage for the creation of the Iliad in the 8th century.

All of the above hypotheses are plausible; none are mutually exclusive. The Trojan War tradition evolved over a long period and any or all of these processes may have played a part. My question here concerns to what extent the Unity might also be shaping historical inquiry. In view of that, the history of conflict in western Anatolia deserves to be treated in some detail.

The conflicts centered on a complex of territories known as the Arzawa Lands, which included five largely independent kingdoms: Mira, Arzawa, the Seha River Land and Wilusa on the coast (listed south to north), and Hapalla (further east). Each was ruled from a capital city: in the case of Arzawa, this was Apasa (the predecessor of Ephesus) where the Cayster River empties into the Aegean. Likewise, Troy is largely accepted as the royal seat of Wilusa and one of the most important cities in western Anatolia in the late Bronze Age.[2]

Acting in concert, these states could and did pose a serious threat to the Hittites. Bryce notes that in the reign of Ḫattušili I (ca. 1650–1620), the first Hittite king for whom written records have been found, there is mention of a military campaign against the Arzawa lands. In the first half of the 14th century, when the Hittites were increasingly distracted by the Hurrians, Arzawa was a great power, such that Amenhotep III (1382-1344) married an Arzawan royal princess to secure an alliance.2 In this period, Arzawa invaded and occupied Hittite territory right up to the Halys River (Hittite name, Maraššantiya; modern Kızılırmak), the western border of Hatti in central Anatolia. In the latter half of the century, the Hittites were able to turn their full attention to western Anatolia and reassert their dominance. Conflict continued until 1280, and thereafter was muted until the Bronze Age collapse a century of so later.

Greece was involved in these conflicts. For example, a Linear B tablet shows “women of Troy” were employed as slave workers in Greece. The tablet calls them “booty,” implying they were captured in raids or taken as “spoils of war.” Other women from Anatolia and the Aegean isles also appear in Linear B texts, indicating the wide scope of these violent activities.[3]

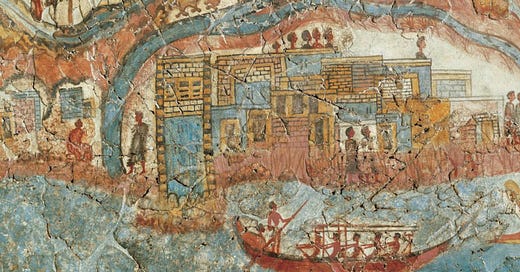

The overall context can best be shown by the timeline below, assembled primarily from Strauss (2006), Kelder (2010), Cline (2013) and Woudhuizen (2018). I have also included dates from the 1st millennium as they relate to the history of the Trojan War saga. All dates, especially before the 1st millennium, are approximate and a discussion of specific events follows.

Timeline Relating to West Anatolian Conflicts and the Trojan War Legend

1430s: Royal marriage between Thebes and Aššuwa; Aššuwan rebellions w/ Mycenaean involvement.

1430–1400s: Attarissiyas, Mycenaean king, active.3

1350s: Thebes conquered by Mycenae; Argive vassal king installed.

1340–1330s: War between Arzawa and Šuppiluliuma I; Kukkunnis, king of Troy, remains loyal to Šuppiluliuma. Šuppiluliuma exiles his queen, Henti, around this time, possibly to Greece.

1315: Mycenaean military support of Arzawa rebellion; Muršili II dismembers Arzawa; loss of Miletus.

1315–1300: Mycenaean takeover of several Aegean isles.

1300: Troy demolished by earthquake; rebuilt by the inhabitants but with a decline in architectural quality.

1295: Muwattalli II ascends the Hittite throne.

Late 1290s–early 1280s: Letter from Theban king to Muwattalli II re: royal marriage w/ Aššuwa.

1280s–1260s: Piyamaradu, Luwian warlord and Greek ally, active within this period.

Late 1280s: Manapa-Tarhunta letter mentions hostilities at Troy.

1280: Treaty between Alaksandu, king of Troy, and Muwattalli II.

1270s: Tawagalawa letter mentions previous Greek-Trojan hostilities over Troy (dating debated).

1272: Death of Muwattalli II, accession of Muršili III; dynastic struggle ends in 1267 with Muršili’s uncle, Ḫattušili III, on the throne.

1250s–1230s: Thebes burned; Orchomenos destroyed; Gla abandoned (all in Boeotia).[4]

1237–1209: King Walmu of Troy forced out by a coup.

1230s: Milawata letter; final loss of Miletus. Piyamaradu mentioned as a figure of the past.

1230–1220: Mycenaean support for an anti-Hittite uprising in western Anatolia; 1225 to 1220 is the last mention of Mycenaean activities in the Hittite record.

1210–1180: The Bronze Age collapse begins during this period.4

1210–1180s: Troy VIIa destroyed by fire (likely sack); rebuilt by the inhabitants.5

1200s-1180s: Wave of destruction on the Greek mainland; Mycenae, Pylos and other palaces destroyed. Effective end of Mycenaean governance and the palace economy swiftly follows.6

1180s: Hittite Empire falls.

1150-1000: Early Iron Age; Troy recolonized from the Balkans; causes unknown. Destroyed by attack or earthquake around 1100and rebuilt by inhabitants; the site is mostly abandoned after 1000.

1150–800: Greek “Dark Ages” (so called).7

800: Greek “Renaissance”; Trojan War narrative based on the end of a heroic age emerges; writing reintroduced.

740s–550s: Trojan War epics (both Homeric and Cyclic poems) composed in this period.

560–527: Pisistratean Recension.8

525–406: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides.

484–322: Herodotus, Thucydides, Aristotle.

350–320: Trojan War epics organized into a formal cycle.9

29–19: Virgil writes the Aeneid.

Our story begins with a marriage between the royal houses of Thebes and Aššuwa.10 Aššuwa was an coalition of twenty-two “lands” (political units) in western Anatolia; Troy was one of its members.11 Cline locates Aššuwa in the southern Troad, between Troy and the Seha River Land. He also observes that “the coalition was apparently rather short-lived… As a separate political entity, Aššuwa really only existed during the mid-15th century.”[5] Woudhuizen has a different take: that Aššuwa was a “great kingdom” encompassing western Anatolia with Arzawa being its core. In 1430 it was led by Piyama-Kurunta, whom Woudhuizen identifies as an Arzawan king.12

Woudhuizen’s conclusion is well argued but regardless of the interpretation, Aššuwa was seeking allies because it planned to rebel against Tudhaliya I/II;13 it may have made overtures to Thutmoses III (1479-1425). As part of the marriage contract, Thebes received three islands in the north Aegean; perhaps Samothrace, Lemnos and Imbros.14 In the rebellion that followed, the Mycenaeans fought on the side of Aššuwa. Accepting the islands made the Theban king a vassal to the Aššuwan king, giving a clear motivation, and probably obligation, on the part of the king of Thebes to aid his in-laws in their war against Tudhaliya. The evidence of their involvement is a Mycenaean bronze sword, one of several taken to Hattušas and offered as spoils of war. The dedicatory inscription reads: “As Tudhaliya the Great King shattered the Aššuwa country, he dedicated these swords to the storm-god, his lord.”[6] As chief religious functionary of his people, a Hittite king would not offer anything but the best to his principle god, so they must have been taken from a worthy foe, such as an army led by a Mycenaean king.

The rebellion was a major conflict involving large forces. According to the Annals of Tudhaliya, Aššuwa rebelled when Tudhaliya I/II was returning from a military expedition against Arzawa, the Seha River Land and Hapalla. Tudhaliya took personal command of his army, attacked and defeated them. Piyama-Kurunta, his son Kukkulli and the other members of the royal family were taken prisoner, along with 10,000 Aššuwan soldiers, 600 chariot teams and their charioteers, and a large portion of the populace with their livestock and possessions. Even allowing for some inflation of the numbers, this indicates a major victory. In addition, Tudhaliya seized the islands granted to Thebes, claiming his victory over the Aššuwans gave him rights to all their possessions. This defeat rankled for the next century and a half, as I will discuss below.

What happened next is not entirely clear, but Tudhaliya appears to have appointed Kukkulli king of Aššuwa, which was reestablished as a vassal state. However, Kukkulli also rebelled and was defeated. Tudhaliya had him executed and Aššuwa was abolished as a political entity. No word of the fate of Piyama-Kurunta or his remaining family is recorded.[7]

The story is just beginning, however. One of the earliest Hittite documents we have that mentions Mycenaeans dates from the reign Tudhaliya’s successor, Arnuwanda I, but deals with events from Tudhaliya’s reign. It is called the “Indictment of Madduwatta.” Madduwatta was possibly an Arzawan prince and certainly a vassal of Tudhaliya who gave his overlord a fair degree of trouble. He came into conflict with a “man of Ahhiya [an early form of Ahhiyawa],” meaning a “king of Ahhiya” or “the ruler of Ahhiya,” named Attarissiyas. From the Indictment, we learn that Attarissiyas fought with Madduwatta, putting him to ignominious flight, so he had to seek safety with his overlord. Undeterred, Attarissiyas attacked again. Madduwatta fled a second time, without even putting up a fight on this occasion, and was saved by the intervention of a Hittite army. The Indictment says that Tudhaliya dispatched a force of chariotry and infantry led by one Kisnapili, who fought a battle with Attarissiyas. Attarissiyas led a force of one hundred chariots and infantry. The Indictment reports that “One officer of Attarissiyas was killed, and one officer of ours, Zidanza, was killed.” Attarissiyas then retired to “his own land” and Madduwatta was restored to his position as a vassal king.[8]

This battle was a sizeable engagement: one hundred chariots was a large force in this day, and we might assume Kisnapili marshalled similar forces. The outcome is vague. An officer on each side was killed, and this has led some historians to conjecture the confrontation was decided by a battle of champions, which was a Bronze-Age custom.[9] In that case, both champions died, leaving the outcome undetermined. On the other hand, the text says “they fought” and then lists two notable casualties, which sounds like a general engagement with the losses to the regular infantry and chariotry being ignored; however, this is not inconsistent with an inconclusive duel. Part of the text is lost so we do not know any further details, but Tudhaliya restored Madduwatta and Attarissiyas “went off to his own land,” so it seems the battle did not go his way.

To explain the significance of the battle between Attarissiyas and Kisnapili requires a brief excursus. The Indictment describes a war, not a skirmish and certainly not a raid. Cline, in Beckman et al, points out that the force Attarissiyas commanded almost certainly exceeded the resources of any one Mycenaean kingdom. The Indictment has been translated as saying “100 [chariots and … thousand infantry].” The number of captives Tudhaliya claims implies about a 19:1 ratio of personnel to chariots, so one hundred chariots suggests a total force of about 2000 men; a comparison with the battle of Qadesh provides a roughly similar ratio.

Qadesh, fought by the Hittites and Egypt in 1274, puts these figures in context. It is the largest engagement we know of from the Bronze Age, and perhaps the largest chariot battle ever fought. The Hittites reportedly fielded an army of 47,500 men.15 To raise these numbers, the Hittites had to resort to extensive use of mercenaries; so much so that Ramesses disdainfully remarked that Muwattalli had to “strip his land of silver” to pay for them.[10] This represents a maximum effort by a Bronze Age superpower.

The only plausible way the Mycenaeans could put a force of nearly 2000 men into western Anatolia would be if it represented the resources of multiple kingdoms. Cline discusses this in some detail and reaches the conclusion that several Mycenaean kingdoms combined forces in an “Ahhiyawa” confederation. Thus, the “kingdom” the Hittites knew as “Ahhiyawa” could refer to this confederation and the “king of Ahhiyawa” would be the king who led it.

As Cline further points out, this conjecture solves a number of issues: unlike the proposition of a “Greater Mycenae” that united most of Greece under its rule, a confederation is consistent with what we glean from Linear B texts, which a unified Greek kingdom is not. The leader of the confederation could be a Great King in the eyes of the Hittites, which the king of a single Greek kingdom would not be. [11] Further, Aššuwa, a contemporary example, and later Greek coalitions such as the Delian league, show this was a well-recognized concept.[12]

It is important to emphasize that this confederation would exist only to support joint military and diplomatic efforts with external powers – no impact on individual sovereignty would be involved and it would not be “PanHellenic” in the sense that would apply in the Classical Era. Each kingdom would maintain its individuality. The king leading the confederation would be restricted to the role of commander-in-chief, but the position would nonetheless confer both substantial prestige and power and thus be the object of internal politics and, potentially, conflict between rival kingdoms. As I shall discuss later, this may bear on the tumultuous relationship between Mycenae and Thebes during this same period.

For the moment, however, I will return to Attarissiyas. That he went back to “his own land” has been interpreted as him returning to Greece, which tends to imply a retreat from Anatolian affairs. We should be careful about reaching such conclusions. As Latacz points out, the Hittite term for “land” is rather vague and need not imply a large territory; indeed, some “lands” appear to be cities.[13] It therefore may be doubted that Attarissiyas retreated to Greece; a force 2000 strong suggests the intent to maintain a permanent presence. He is thought to have used Miletus, which was already under Greek control, as a base of operations. It was established as a Minoan colony ca. 1600 and excavations indicate that Greeks were already settled there ca. 1450.[14] Although Miletus’ status did fluctuate, the Mycenaeans seem to have usually been able to exercise control over it until the late 13th century, giving them a strategic foothold from which their forces could operate.16

The last we hear of Attarissiyas, he was raiding the Cypriot coast, further suggesting he remained in Miletus. Madduwatta is said to be conducting also raids on Cyprus. Could he have made peace with the Greek leader and they embarked on joint operations? It is possible.[15] Cyprus was a Hittite dependency, so such raids constituted economic warfare, which Attarissiyas had engaged in on the Anatolian mainland. The aftermath is unknown, as he and Madduwatta disappear from history at this point.

The “Indictment of Madduwatta” is the first textual evidence we have of Mycenaean forays into the Anatolian mainland. Attarissiyas is the first named Greek leader involved with western Anatolia that we know of, and he seems to have had a fairly long career. He has attracted special interest for another reason: Attarissiyas, his Hittite name, has been interpreted as the Greek name Atreus by some scholars. Martin West suggested a link based on the Greek patronymic Atreïdēs, derived from the Mycenaean *Atrehiās.[16] It has also been suggested Attarissiyas may indicate “Of Atreus,” meaning of that family, as opposed to his name. Either way, we have a Mycenaean king with a suspicious name fighting in western Anatolia with forces large enough to attempt recovery of lost lands and avenge an insult to a Greek queen.17

The rest of the century was tumultuous on both sides of the Aegean. In Anatolia, the Hittites were having major problems with the Hurrians, which allowed Arzawa to become a great power and led to the “dark days of Tudhaliya III’s reign,” in the words of Bryce.[17] We might wonder what, if anything, the Mycenaeans had to do with this, but the record is silent. Tudhaliya’s days were numbered, though. His younger brother, the successful general Šuppiluliuma, overthrew him and seized the throne, reigning as Šuppiluliuma I (1344–22). He would pay for it in the end (so his son Muršili II says: Šuppiluliuma died of a plague brought back by Egyptian prisoners, which was interpreted as divine punishment for deposing his brother),18 but he was a great, if ruthless, ruler, defeating the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni and ending that threat forever.

In order to buy Babylonian neutrality while he dealt with Mitanni, it appears Šuppiluliuma exiled his queen, Henti, to marry Malnigal, daughter of king Burna-Buriash II. The text is incomplete, but Henti may have gone to Greece. If this is correct (Bryce and others support it) one wonders what effect the presence of an exiled Hittite queen, the mother of Šuppiluliuma’s heirs, might have had on relations between Hatti and the Mycenaeans.[18]

On the Greek mainland, there was trouble between Mycenae and Thebes. According to Woudhuizen, the royal house of Thebes was destroyed by Mycenae ca.1350 and an Argive vassal king named Thersander was put on the throne.[19] This situation may not have lasted, as a descendant of the Theban king who contracted the dynastic marriage in the 1430s was ruling Thebes in the 1290s.

Around this same time, Arzawa started another war. Again, we might wonder if the Mycenaeans were involved, especially if Henti was indeed resident there. Of particular interest though, Kukkunnis, king of Troy, remained loyal to Šuppiluliuma, in opposition to Arzawa, which would also mean in opposition to the Mycenaeans, who were Arzawa’s allies throughout this period.

The next incident we know of is the Arzawan rebellion of 1315. This event falls in the reign of Muršili II, and has been dated by a solar eclipse, giving us one of the few firm dates in our timeline. Muršili came to the throne at a young age, which led to him being tested early on by adversaries and potential rivals alike. He was more than equal to the task. He fought against the Kaska (an often rebellious people in northern Anatolia who may have played a role in the Hittite collapse) and when Arzawa rebelled, he defeated the kingdom and destroyed its capital at Apasa. Considering its history, Bryce describes Arzawa as the “biggest thorn in the Hittite side during the first half of the Late Bronze Age.” Muršili was not kind in victory. He had the inhabitants (including some who had taken refuge on a nearby mountaintop and had to be starved out) taken to Hatti in a mass evacuation. His annals claim he deported 60,000 or 66,000 persons.[20]

Muršili dismembered Arzawa and gave most of its lands to the kingdom of Mira, which had remained loyal.[21] In the end, this might not have been the best decision, as Mira later became a powerful kingdom in its own right and challenged the Hittites for supremacy. But as is often said, it must have seemed like a good idea at the time.

The Mycenaeans were involved in this rebellion; the relevant text (KUB XIV 15 I, 23–26), mentions troops being mobilized, the Arzawan king, Uhhaziti, and the king of Ahhiyawa. It reports the Mycenaeans seized some Aegean islands around this time, as well (the text does not say which islands these were). Clearly, the Mycenaeans were busy in western Anatolia during this period and we see the likely consequences in a destruction layer at the site of Miletus, which is probably due to Muršili retaliating for the Mycenaeans supporting Arzawa’s rebellion. Uhhaziti escaped with his sons to a Greek-held island in the Aegean, which could not have improved Muršili’s disposition on the matter.[22]

Three Letters and a Treaty

It is against this backdrop that the king of Thebes wrote Muwattalli II (1295–1272) about the disputed islands his ancestor received from the dynastic marriage with Aššuwa. The date of the letter is undetermined, but it was probably sent early in Muwattalli’s reign. The Theban king claimed they had been ceded to his ancestor before the rebellion and belonged to Thebes at the time of Tudhaliya’s victory. The letter was a diplomatic attempt to recover the islands about 150 years after the fact.[23]

The outcome of this exchange is unknown, but there is a hint that another dynastic marriage might have been involved: a single item in a fragment about Helen and Paris meeting a king named Motylos on their way back to Troy. It has been suggested that Motylos could refer to Muwattalli.[24] While the slimmest of evidence, if an agreement did result from this exchange, a royal marriage to seal it would not be unexpected.

Whatever the outcome, our next evidence is a letter sent by the king of the Seha River Land to Muwattalli, his overlord, in the late 1280s. It is called the “Manapa-Tarhunta letter” after its sender and is of great interest. Manapa-Tarhunta wrote of a military action ongoing at Troy and complained about troubles he suffered at the hands of Piyamaradu, a renegade Luwian warlord.19

Piyamaradu is a redoubtable character who might be considered either the hero or villain of our story, depending on one’s point of view. He has been called a general, an adventurer, a brigand, a notorious freebooter and a troublemaker. All of these descriptions seem apt. For years, he exercised widespread power in western Anatolia, operating out of Miletus, which was ruled for an extended period by Atpā, his kinsman by marriage. He enjoyed Mycenaean support throughout his career, which resulted in him being mentioned in several Hittite diplomatic texts and even a votive prayer by Queen Puduhepa, wife of Ḫattušili III (1267–1237), asking the gods to deliver Piyamaradu to them. Perhaps no one else of his era had such an extraordinary career, successfully defying Hittite authority for decades and surviving all attempts to apprehend him. Bryce wonders if he may have ended his life comfortably on an island refuge given him by his Mycenaean supporters “whose interests he served so well.”20 For those sympathetic to the Greek cause, it is a charming thought.

Returning to Manapa-Tarhunta, his letter informs us that Piyamaradu humiliated him and placed his kinsmen Atpā “over him” (that is, Atpā became de facto ruler of his kingdom), then conquered Lesbos and handed it over to the Mycenaeans. As usual, the letter is fragmentary and requires much interpretation. Some read it as Piyamaradu having taken Troy, Manapa-Tarhunta being tasked with ousting him and defeated, so Muwattalli sent troops to accomplish what Manapa-Tarhunta had failed to do. In addition, Manapa-Tarhunta said he was “ill” and could not accompany the Hittite troops to Troy. As Bryce remarks, this is a lot to read into a short fragmentary text.[25] All that can be said with any confidence is:

1. Manapa-Tarhunta wants to reassure Muwattalli that things are fine in his land.

2. He has had problems with Piyamaradu and Atpā, who “humiliated” him.

3. Hittite troops under a commander named Gassus or Kassu came to the Seha River Land, then departed to fight at Troy, or perhaps to return to Troy.

4. He claims illness in a way that suggests he is making an excuse for why he did not accompany the Hittite force going to Troy.21

The references to Piyamaradu and Atpā come after a paragraph divider in the text which could mean Manapa-Tarhunta is discussing a new subject, so his comments about Troy may have nothing to do with Piyamaradu and his activities. Bryce concludes that while “Piyamaradu may have been operating in the region of [Troy] as the agent of the [Ahhiyawan] king”, there is nothing to clearly link him with Troy in the text, which is certainly true.

On the other hand, his activities coinciding with hostilities ongoing at Troy raises the possibility that his campaign in the Seha River Land was part of a combined operation. The Mycenaeans were certainly capable of planning such an operation and it would be of obvious benefit to pacify a hostile kingdom immediately to the south, and also to divert Hittite forces. Lesbos would make an excellent staging area, logistical base and, if necessary, secure area to retire to. Overall, such a strategy makes good sense. While it cannot be proven, it is suggestive.

Next we have the Alaksandu Treaty, after the Trojan king Alaksandu who sealed it with Muwattalli. The treaty has been dated to 1280, giving us another chronological fix, and it marks Troy being formally incorporated into the Hittite empire. The treaty lays out the obligations of Alaksandu and his heirs, and what they can expect from Muwattalli and his heirs in return. It is quite long, detailed and specific, and presents a number of points of particular interest.[26]

First, the preamble talks about the relationship between the rulers of Troy and the Hittite throne going back to the first Hittite kings. It makes the point that the Trojan rulers have been generally loyal during this whole time, which put them in opposition to other west Anatolian kingdoms, which were prone to insurrection.22 It also says that Muwattalli aided Alaksandu militarily: “I, My Majesty, protected you, Alaksandu, in good will because of the word of your father, and came to your aid, and killed your enemy for you…”[27] Third, it enjoins Alaksandu to keep an eye on his restless neighbors, report any treasonous activity and be prepared to support Muwattalli with troops as required. Clearly, Muwattalli was deeply concerned with maintaining peace in western Anatolia during a time when tensions with Egypt were ramping up.23 As we know, they would explode into open warfare from 1275 to 1269.

So while Alaksandu needed Muwattalli’s support, Muwattalli equally needed Alaksandu as a loyal vassal to help him keep control of volatile western Anatolia while Muwattalli focused elsewhere. Both Muwattalli and Alaksandu had excellent reasons to seek this agreement. It is therefore interesting which of those “restless neighbors” Alaksandu was to report on. They are listed so there can be no mistake, but curiously, the Mycenaeans are not among them. Given the amount of trouble the Mycenaeans had been to the Hittites for over a century and their recent (and as it turns out, ongoing) support for Piyamaradu, it would be reasonable to expect the treaty to mention them as well. That they were left out suggests that the Mycenaean problem had, for the time being at least, been resolved.

Kelder supports this, saying, “one would expect references to other powers in the region, especially to the formerly troublesome Mycenaeans.” Since they are not mentioned, but other potentially troublesome kingdoms are, Greece “apparently was of no threat to the Hittites at that time, which could be achieved only by means of some kind of understanding.”[28]

Additional support for this view comes from the third and last Hittite document related to these events. This letter, called the Tawagalawa letter, is from a Hittite king to his Mycenaean counterpart, acknowledged as a Great King. It is the third and last tablet of a long document, so we cannot read who the sender or recipient was. In it, Tawagalawa is identified as the “brother” of a Mycenaean king, but Woudhuizen interprets this usage as a royal courtesy, where kings referred to each other as “brother,” not as indicating they are actually siblings. In Woudhuizen’s judgment, Tawagalawa was Theban king who was a vassal to the king of Mycenae.[29] His name is interesting: it appears to be the Hittite for Eteocles, the name of the mythic king of Thebes.

The letter covers a lot of ground. The beginning of the text describes unrest in the Lukka Lands (later Lycia), located in southwestern Anatolia; the Hittite king went there to handle the situation. He states that Tawagalawa also went there at the request of some Anatolian rebels he alleges Tawagalawa was helping escape to Mycenaean territory. But the inhabitants appear not to have been of one mind; the Hittite king says others appealed to him for aid because Piyamaradu had been forcibly removing them from their homes.24

However, the main purpose of the tablet is to secure Mycenaean cooperation in dealing with Piyamaradu. Kelder notes Tawagalawa was a major political figure at the time, but he was of less concern to the Hittites than Piyamaradu.25 Accordingly, the Hittite king undertook a campaign to apprehend Piyamaradu, which he describes in his letter. He traveled to a town, Wiliwanda, from which he sent a message to Piyamaradu, attempting reconciliation. Piyamaradu, who occupied a stronghold called Iyalanda, rejected the offer and when the king approached, he attacked. The Hittite king defeated him after a stiff fight and “destroyed the land of Iyalanda.” Piyamaradu escaped to Miletus, which was ruled by Atpā at this juncture. The Hittite king pursued him, sending ahead a demand that Piyamaradu give himself up, promising safe conduct. Piyamaradu refused, so he sent a message to his “brother” king asking for Piyamaradu to be surrendered.26

On receiving the Hittite request, the Mycenaean king sent Atpā orders to place Piyamaradu in Hittite custody. Given the kinship between Atpā and Piyamaradu, one wonders how serious this order was, but a notice was sent to the Hittite king about it. Before the order could be acted on, Piyamaradu departed to one of the Greek islands. Balked at Miletus, the Hittite king asked his Mycenaean counterpart to send Piyamaradu a message. The translation in Beckman et al reads: “O my brother, write to him this one thing if nothing (else): ‘Get up and go to Hatti. …’” He then lists other options he wants the Mycenaean king to convey, all of which urge Piyamaradu to leave Mycenaean territory. The Hittite king ends this message with:

“The King of Hatti has persuaded me [the Mycenaean king] about the matter of the land of Wilusa concerning which he and I were hostile to one another, and we have made peace. Now(?) hostility is not appropriate between us.” [Send that] to him [Piyamaradu].[30]

The upshot is there was a past conflict between the Hittites and Mycenaeans over Troy and the Hittite king does not want to risk Piyamaradu’s activities leading to another. He wishes the Mycenaean king to make it clear to Piyamaradu that he (the Mycenaean king) will not support Piyamaradu because he and Hatti have made peace. Despite the threat Piyamaradu posed, and which Hatti took quite seriously, the Hittite king, while complaining and chiding his “brother” king for supporting Piyamaradu, is seeking a diplomatic, not military, solution.

With its mention of a past “matter” over which Hatti and the Mycenaeans were “hostile to one another” this letter has sometimes been interpreted as a “smoking gun” for the Trojan War. But the exact nature of the conflict is vague because according to Bryce and Beckman the Hittite word in the text can be translated as anything from “outright war, a skirmish or two, or merely a verbal dispute conducted through diplomatic channels.”[31] The question turns on who sent the letter. Most historians have assigned it to Ḫattušili III, Muwattalli’s brother and his second successor, who ruled 1267–1237, and it has been dated as late as 1250. Beckman et al state parenthetically that they assume it was written by Ḫattušili III, but acknowledge it could be Muwattalli, and Kelder observes that the exact order of events is unclear.[32]

It seems unlikely a Hittite king would engage in a trip across Anatolia to capture a rebel while Hatti and Egypt were at war, suggesting the journey took place before 1275 or after 1269. The Alaksandu Treaty may have provided Muwattalli with an opportunity to deal with the “unfinished business” of Piyamaradu, with the unrest in the Lukka Lands serving as either a prompt or pretext. It makes sense that Muwattalli would want Piyamaradu neutralized in a time of heightened tensions.

The status of Miletus provides an additional potential datum. As noted, Muršili II took over Miletus because of Mycenaean support for the Arzawan uprising, but at some point they regained control. Bryce suggests Muwattalli “ceded [Miletus] to the Mycenaean king with the understanding that this would still his hunger for territory on the Anatolian coast.”[33] Anatolian Miletus does appear in the list of Trojan allies in the Iliad; a hint that it belonged to the Hittites during the 1280s.27 While shaky evidence, it is not impossible that the cession was part of the deal that concluded the conflict over Troy.

Woudhuizen makes the most specific case for the Tawagalawa letter being written by Muwattalli. He cites Oliver Gurney (2002) and mentions that Kelder himself concluded that the Manapa-Tarhunta letter and the Tawagalawa letter date from “around the same time.” Because Muwattalli removed Manapa-Tarhunta and made Masturi king of the Seha River Land, Woudhuizen says that “instead of down-dating the [Manapa-Tarhunta] letter this leaves us no other option than up-dating the [Tawagalawa] letter.”28 If Muwattalli sent the Tawagalawa letter, we are looking at one armed conflict at Troy involving the Mycenaeans in the years before the Alaksandu Treaty, that was resolved by negotiation. This is my assessment, based on the new dating and circumstances described. Woudhuizen reached the same conclusion.[34]

The forgoing allows us to construct a timeline without resorting to undue speculation:

Mycenaean military support of Arzawa rebellion results in the loss of Miletus (1315).

Mycenaean takeover of several isles (1300s).

Muwattalli II ascends the Hittite throne (1295).

Letter from Theban king to Muwattalli regarding lost islands (1295-early 1280s).

Piyamaradu and Atpā active against Manapa-Tarhunta and Piyamaradu conquers Lesbos; Hittite forces visit the Seha River Land, then go to Troy (late 1280s).

Alaksandu Treaty concluded (1280).

Muwattalli II replaces Manapa-Tarhunta with Masturi; unites with him by marriage (1280).

Tawagalawa letter from Muwattalli to a Mycenaean Great King; Miletus is back in Greek hands and ruled by Atpā. Piyamaradu is forced to take refuge on Greek controlled islands. Mention of a previous conflict over Troy which was resolved by negotiation (1270s).

By this reckoning, a period of rapprochement followed the Alaksandu Treaty. This makes sense, as both the Mycenaeans and Hittites had “bigger fish to fry.” The Hittites were embroiled in the war with Ramesses II from 1275 to 1269. To the east, the Assyrians were waxing powerful and becoming more aggressive. Muwattalli died in 1272, leading to a dynastic struggle which ended when his brother Ḫattušili openly rebelled against Muwattalli’s heir, Muršili III (Uhri-Teshub) and seized the throne in 1267. This usurpation unsettled the empire and would dog the Hittite royal family for years to come.

Things were not entirely quiet in western Anatolia, either. We have a record of the Trojan king, Walmu, being forced out by a coup between 1237 and 1209. He took refuge in a nearby territory and was subsequently reinstated by the Hittite king, indicating the Alaksandu Treaty remained in effect through most of the 13th century. Who was responsible for the coup is unknown, but there is no evidence of Mycenaean involvement.

On the Greek side, Thebes was burned in the latter half of the century; Orchomenos and Gla “went to rack and ruin” amid signs of strife throughout the mainland.[35] Within a generation, Mycenaean civilization would be showing signs of collapse. The Milawata letter, dating from the 1230s, mentions the Mycenaeans but the Mycenaean ruler has been struck off the list of Great Kings, indicating he no longer ranked as one (other reasons have been advanced). There is a record of Mycenaean support for an abortive rebellion in the Seha River Land sometime between 1230 and 1220. The last mention of the Mycenaeans in Hittite documents concerns restrictions imposed by the Hittites on Mycenaean shipments to Assyria.29 From about 1225 to 1220 on, it seems the Mycenaeans were in no state to meddle in Anatolian affairs.

To sum up this entire history, the Mycenaeans were present in western Anatolia from the 1430s to about 1225 or 1220, and over most of that period they were able to act directly in the region, as well as exert their influence through local rulers and by supporting rebellions. The late 15th century to the early 13th century was the period of greatest activity. After about 1260, external forces combined with internal divisions came to dominate both the Hittite empire and the kingdoms of mainland Greece. After about 1230, collapse on both sides was inevitable.

The War for Helen: A Bronze Age “Hundred Years War”?

She is still there, since nations that brave each other for markets, for raw materials, rich lands, and their treasures, are fighting, first and foremost, for Helen.

Rachel Bespaloff.30

We have finished Round 1 in our match with the Old Man of the Sea. What clues have we gained, if any? I believe there is at least one: the idea of a Trojan War after the Alaksandu Treaty can be dispensed with. I have two reasons for proposing this, and a caveat I will address when I discuss the Iliad in context. Both reasons are straightforward.

First, on the evidence of the Tawagalawa letter, the Alaksandu Treaty was followed by a period of rapprochement, as I mentioned previously. I also noted the letter shows the Hittites and Mycenaeans were in regular diplomatic contact which would help to keep disagreements from escalating. Muwattalli had the Egyptian war on his hands and Muršili III was too preoccupied during his brief reign to court more trouble; a renewed conflict with Greece was the last thing he needed. The same would apply to Ḫattušili III, who had to solidify his position, contain the Assyrians and devise a lasting peace with Egypt. Further, the Alaksandu Treaty appears to have worked; as we saw, it was in force in the last third of the century. Bringing Troy into the Hittite fold as a loyal vassal state may have quelled the rebellious impulses of its neighbors, at least until mid-century. Lastly, it should not be overlooked that in addition to their martial prowess the Hittites were effective diplomats. They often attempted to defuse a potential crisis, as they did at least once between subject kingdoms, and they concluded a landmark treaty with Egypt.31 Their documents also show examples of clemency toward kings and clients that defected from them; Muwattalli even tried to reconcile with Piyamaradu. Maintaining peaceful relations with the Mycenaeans would not be remarkable if they felt it served their best interests.

From the Mycenaean’s perspective, as long as they were not provoked, they would seem to have little incentive to pursue hostilities with Hatti in the years after the Alaksandu Treaty. It is reasonable to conjecture they received a satisfactory benefit from the settlement of the conflict, given the cordial relationship between Tawagalawa and Muwattalli. By around 1260, their internal divisions might have reached the point where foreign ventures were no longer possible; they may well have lost the ability to effectively project power overseas. After 1250, this is almost certainly the case. The Ahhiyawa Confederation had collapsed by this time. Although the Mycenaeans would make mischief in the Seha River Land in the 1220s, anything that might qualify as a war was beyond their capabilities.

I am not making a new argument here; others have been over this ground and countering opinions have been offered. Latacz suggests an attack on Troy in response to the loss of Miletus in the 1220s might be the historical inspiration for the Trojan War,[36] but this idea has not been embraced. It has even been suggested the Mycenaeans might have attacked Troy because of the unrest at home, or that the unrest was encouraged by their military forces being engaged at Troy. Taking into account the conditions in Greece at the time, it is difficult to give these latter proposals serious consideration in the absence of evidence.

My reasoning does not rule out the “Song of Roland” scenario, however. A band of warriors could, in theory, have launched a minor attack on Troy. It has been speculated that the ousting of Walmu could have included a force from Greece.32 What would prevent any such action from metastasizing into a legend crafted by a people whose society was coming apart at the seams?

This leads to my second reason: there is simply no reason for it. Stepping back and looking at the history previously related, what stands out? A war – not of ten years but of 150 years – every bit as grand, every bit as romantic, every bit as epic as the Trojan War legend we know.

It is a Bronze Age “Hundred Years War” that began with a royal marriage had no lack of drama: spirited rebellions, lost lands, pitched battles, dispossessed queens, ruthless emperors, palace intrigues, perilous journeys, daring escapes, great heroes, cunning rogues…

Lest I be accused of sounding overwrought, let us pause. The crux of the problem is how we approach this history, fragmentary and disjoint as it is. To us, it seems more acceptable to see wars as being fought over resources, abstract concepts like national interests or security, or cold-hearted geopolitical considerations; as sober historians, we tend to recoil from romance.

The letter from the unnamed Theban king to Muwattalli II regarding the lost Aegean islands fits neatly into this modern conception: it was a conflict over territory. But we must not allow this conception to blind us. As Barry Strauss observes in his podcast, Antiquitas Season 1, Episode 1, in the Bronze Age a primary casus belli was “He dissed me!” So while a war for Helen may seem unlikely or uncomfortable to us, to the ancient Greeks it made perfect sense.

Hittite records, in so far as they are available to us, are silent on the fate of the Theban queen over whom this war may have started, but the Mycenaeans knew and would not have forgotten it. However, unlike the Hittites, they did not write their history down; they sang it and it is echoed in both Hesiod and the Iliad. Rachel Bespaloff has it right. What poet could look at such a time and not see the epic potential of it? What poet could fail to sing about it when they did?

Now I shall move on to what may be the second clue gleaned from our match.

A Bronze Age “Wars of the Roses”?

As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, Hesiod, in Works and Days, speaks of the race of heroes, called demi-gods, the fourth race Zeus created and the immediate predecessors of Hesiod’s age, who came to a catastrophic end. He does not directly blame Zeus for their demise, nor does he say anything about Gaia being overburdened; perhaps he had not heard that ancient Mesopotamian myth. He says “ugly war” destroyed them, implying they were warlike and loved “fearful fighting” too well. Specifically he says (Martin West’s 1988 translation):

[U]gly war and fearful fighting destroyed them, some below seven-gated Thebes, the Cadmean country, as they battled for Oedipus’ flocks, and others it led in ships over the great abyss of the sea to Troy on account of the lovely haired Helen.

Thus (as mentioned previously), there was once a tradition that two great wars led to the end of the heroic age: the Trojan War and Theban war. Both had two episodes; in the Iliad, the attack on Troy by Heracles is the first and Agamemnon’s Trojan War is the second. The first Theban war ended with the defeat of seven heroes (one for each gate of Thebes), who were avenged by their sons ten years later. Both the descendants of Heracles and the seven heroes (the most prominent of which is Diomedes, king of Argos and son of Tydeus) are present in the Iliad and recite their father’s exploits. The tale of the Theban wars did not survive; by the time the Cypria was composed in the first half of the 6th century, it had been eclipsed by the Trojan War, which thereafter became to be thought of as the sole cause of the end of the heroic age (perhaps the idea a civil war was partly responsible was no longer palatable to the Greeks).

There were at least two historical Theban wars; as discussed, Thebes was defeated once in the 14th century when a Mycenaean puppet king was installed, and again in the 13th century, when it was razed to the ground. The latter event has been tentatively blamed on internecine warfare, but the involvement of Mycenae cannot be ruled out, especially considering the 14th century conflict.33 If Mycenae was to blame, what would be the cause of this enduring quarrel?

Most historians take the view that Mycenae was the dominant kingdom in Greece during the late Bronze Age. Kelder proposed a “Greater Mycenae” (referred to previously); most scholars reject this, but some, including Woudhuizen, are comfortable with the other Greek kingdoms being essentially vassal states.[37]

Other scholars dispute the primacy of Mycenae. They argue that Thebes could have been the dominant kingdom in Greece during at least part of this period. Latacz highlights the power of Thebes and that it controlled more territory than any other kingdom in Greece.[38] Its leading role in western Anatolia is highlighted in history and literature. The grand fleet of “1000 ships” gathers at Aulis, a port belonging to Thebes, not at a port controlled by Mycenae. Also in the Iliad, Thebes is held up as an icon of wealth along with Orchomenos.34 Thebes was once considered the equal of Troy in causing the downfall of the demi-gods. Thebes’ status is therefore well supported, and the fact there is an unresolved debate over which kingdom was more powerful, and at what times, suggests the following answer: both.

Consider the Ahhiyawa confederation: the kingdom that led it would be the first kingdom in Greece and its king was entitled to be considered a Great King, at least in the early 13th century. Thebes and Mycenae were, per their history of conflict, bitter rivals. If there was an Ahhiyawa confederation, as is most likely, Thebes and Mycenae, as the two largest and richest Greek kingdoms, would vie for control of it. Mycenae may have had the upper hand much of the time, but probably not all of the time, leading to a mixed historical record. Mycenae eventually won out, but it was a Pyrrhic victory, for Mycenae collapsed and was destroyed not long after.

Could this be a Bronze Age “Wars of the Roses” in which two royal houses fought – sometimes literally and other times diplomatically and/or economically – for control of the Ahhiyawa confederation? If so, this conflict, which must have lasted over a century, could have eventually led to mutual exhaustion and hastened the collapse of Mycenaean civilization. The evidence is not conclusive, but I believe it merits consideration. With these two clues in mind, it is time to look at the Iliad.

This concludes Part 2

References

[1] Alexander (2009, 1).

[2] See Bryce (2006, 111) and Latacz (2004).

[3] Alexander (2009, 5).

[4] Woudhuizen (2010, 144).

[5] Cline (2013, 59).

[6] Cline (2013, 59).

[7] Cline (2013, 58-59).

[8] Kelder (2010, 23-24) cites KUB XIV 1, §12, 60–65, adapted from Beckman, 1996.

[9] Strauss (2006, 119).

[10] Bryce (2006, 197).

[11] Beckman et al (2011, 5), citing Kelder (2005 and 2010).

[12] Beckman et al (2011, 5-6).

[13] Latacz (2004, 94, 98).

[14] Bryce (2006:185-201); Kelder (2010, 24.)

[15] See Strauss (2006, 35) and Kelder (2010, 24).

[16] West (2001, 262–66).

[17] Bryce (2006, 151.)

[18] Bryce (1999, 172-4).

[19] Woudhuizen (2018, 110).

[20] Bryce (2006, 120); Bryce (2019, 110).

[21] Strauss (2006, 99).

[22] Bryce (2006, 146); Kelder (2010, 26).

[23] Cline (2013, 60-61).

[24] West (2013, 93).

[25] Beckman et al (2011, 144); Bryce (1999, 227; 2006: 249).

[26] The existing text of the treaty, translated by Frank Starke, can be found in Latacz (2004, 103-110).

[27] Cline (2013:62.)

[28] Kelder (2010, 27).

[29] Woudhuizen (2018).

[30] Beckman et al (2011, 115).

[31] Beckman et al (2011, 121).

[32] Beckman et al (2011, 120-121); Kelder (2010, 28-29).

[33] Beckman et al (2011, 121).

[34] Woudhuizen (2018,109).

[35] Woudhuizen (2010).

[36] Latacz (2004, 286

[37] See Kelder (2010), Woudhuizen (2010 and 2018) and Cline (Beckman at al, 6.).

[38] Latacz (2004; 126, 238, 241-3).

Footnotes

For decades, the identities of Wilusa and Ahhiyawa were contentious. However, they are now been established beyond a reasonable doubt and the question may be considered settled, though popular sources still echo doubt. See Beckman et al (2011, 6), Bachvarova (2016) and Woudhuizen (2018, 28).

Tarkhundaradu, an Arzawan king known from the Amarna letters, was considered a Great King, at least in Egyptian eyes (Kelder 2010, 26; Woudhuizen 2018, 115).

Kelder (2010, 25) says “around 1430 BC.” Strauss (2006, 35) says “shortly before 1400 BC.” West (2001, 264) suggests 1390-1370 BC. There is substantial uncertainty on this point.

The Bronze Age collapse was a process that happened over time, at different rates in different places. It is thus best not to think of specific dates for it. See Cline (2021) for more discussion.

Around 1180 is considered the latest possible date, based on pottery finds; it might be a early as 1210.

The palace economy was a key feature of Mycenaean civilization (and similar ancient civilizations). It was not a market economy but a redistributive one in which all economic activities were administered by an elite under the control of a ruler. Goods and services, as well as land, were apportioned within a palace’s territory without being assigned values to create the equivalences needed for market exchange.

Neither “Dark Ages” nor “Renaissance” are very satisfactory terms. Burgess (2001,2) rejects them outright and for good reason. At best, they are labels for two specific periods in Greek history that have become familiar through use and I employ them in that sense only.

West (2011, 74) assigns this activity to Pisistratus’ son, Hipparchus, in the late 520s. Nagy (2001) argued written texts of “Homer” did not exist before this period which West, in particular, disputed.

According to Aristotle this was done by one Phayllos, about whom we know nothing else (West 2013, 23-25).

Woudhuizen concludes that Thebes was involved based on lapis lazuli cylinder seals found there, including a seal with Luwian hieroglyphics and the image of a king. He says the Aššuwan king gave the seal to the Theban king to allow him to exercise authority over the islands he received (Woudhuizen, 2010, 144; 2018, 65).

Most of the members of Aššuwa have defied identification. Latacz suggests this may be because the Hittites included all political units with Aššuwa’s borders regardless of size to enhance the stature of the victory. (Latacz 2004, 98). Woudhuizen places four members in Arzawa (Woudhuizen 2018, 34).

“[T]he [Aššuwan] League consisted of a coalition of forces running from Lukka in the southwest to [Wilusa] in the northwest, and hence comprised western Anatolia in its entirety.” (Woudhuizen 2018, 55, 71).

It is unclear if he was the first or second Hittite king of this name, hence the designation I/II. (Cline 2013, 57).

Strauss (2006, 19). These are strategically useful islands, but hardly garden spots (in the economic sense).

Strauss (2006, 41). At Waterloo, Wellington’s British forces (as opposed to allied) numbered 24,500 men.

Kelder (2010, 24). Woudhuizen believes Thebes may have played a “crucial role” in this regard (Woudhuizen 2010).

Recall that Piyama-Kurunta and family were taken prisoner; that would have included his queen. One might expect the king of Thebes would not take his daughter being a Hittite captive lying down; the same could apply to his successors. Here the literary evidence may inform the historical record.

See the “Zidanza Affair,” in which Šuppiluliuma accused the Egyptians of murdering one of his sons.

Cline (2013, 62). It has been proposed Piyamaradu may be Uhhaziti’s grandson (Woudhuizen 2018).

Beckman et al (2011, 252). Queen Puduhepa’s prayer also discussed here.

However, Manapa-Tarhunta is known from Muršili II’s reign, making him elderly, so his illness may have been genuine. In the end, though, his behavior seems to have prompted Muwattalli to remove him and place his (likely) son Masturi on his throne, as someone more effective.

There is a good reason for Troy’s loyalty: it was never an expansionist military power. Its power came from being a commercial center and the most important entrepôt in northwest Anatolia. As such, it was useful to everybody and gained nothing from antagonizing the Hittites, who in turn would leave Troy alone as long as they profited.

The Greeks were not alone in meddling with western Anatolian politics; Ramesses II corresponded with the king of Mira, no doubt hoping the latter would act to distract Hatti for Ramesses’ benefit. (Strauss 2006, 163.)

Beckman et al (2011, 101-122). This confusion may explain Kelder’s interpretation that the letter complained about laborers being recruited for Greek projects and Tawagalawa was responsible for this. (Kelder 2010, 27.)

Tawagalawa is shown to have been on close personal terms with the Hittite king and the letter’s overall tone is friendly. It also shows that the Hittite and Mycenaeans were in regular communication with each other.

It may be worth reiterating that this “brother” king would be the king leading the “Ahhiyawa” confederation.

The Iliad (2:867) says Miletus was held by the Carians “wild with barbarous (βάρβαροϕώυωυ) tongues” (Fagles 1990, 127). West (2011, 126) suggests this may be to emphasize Miletus was not Greek at this time.

Woudhuizen cites Bryce (2010, 227). Bryce comments that Muwattalli married Masturi to his sister, a “signal honor.” (Bryce 2006, 158).

Cline (2021, 93). Latacz (2004, 127). This appears in a Hittite treaty with a vassal that they variously date from “about 1225” (Cline) to 1220 (Latacz).

Weil et al (2005, 63).

Ugarit and Amurru nearly went to war around 1230, but were prevented by Hittite negotiators.

It might be supposed that if the Mycenaeans were involved the Hittites would have mentioned the fact.

See Strauss for the comment about the possibility of internecine war (Strauss 2006).

The Iliad we have says Egyptian Thebes but this must be an interpolation. In context, Boeotian Thebes is clearly meant. How it later came to say Egyptian Thebes is a topic for another essay.