All-Devising Zeus

A Tale of Analytic Overreach.

Note: this essay discusses the myth that Zeus sexually assaulted Nemesis to conceive Helen. If you are sensitive to this topic, proceed with caution, if at all.

In the late 1980s, not yet midway into my former career, two installations were observed that caused considerable consternation.1 Various hypotheses as to their nature were proposed, some more elaborate than others, and often rather sinister. Despite not being the most senior analyst at the time it became, due to my background, my task to produce an assessment of these installations, which I did. Other assessments had been, or were being produced, including two from my own organization, besides my own. These other assessments were quite detailed and well argued, and reinforced the sinister nature of these installations.

My own conclusions, which did not support a sinister mission but one that was notably prosaic, were not met with universal approbation, and drew open derision from one influential quarter. This reception, and my relative lack of standing, made this episode one of the more challenging of my career. Vigorous defense of my position was required, and was made. Thus, and perhaps ignobly (for I’m only human), when new information came to light a few years later, proving my assessments to be correct in both cases, I was probably more gratified than I should have been.

But in addition to realizing that I should be more humble, even – especially – when I was right, another principle was illuminated. The heart of the problem was that we were short on data and long on appearances. By that, I mean given the lack of data, nearly everything appeared to be significant, and so was assumed to be meaningfully related, thus indicative of some greater hidden whole that needed to be exposed. This resulted in what little data we had being overinterpreted, in pursuit of this notional whole, which in the end, turned out to be rather humdrum. The appearances which caused such consternation were not the result of some sinister grand scheme, but simple mechanical limitations and workaday convenience. Sparse data made postulating relationships easier and more inviting, so things that were assumed to be connected either weren't, or if they were, not in the manner that had been proposed. (Again, such connections, where they existed, were mundane.)

This tendency to run ahead of the data may occur whenever data are ambiguous, contradictory or sparse. We all wish to find clarity and coherence in the analytic issues we take on – that is our job. But, just as we should avoid undue reticence in reaching conclusions, overinterpretation should equally be guarded against. To enlarge on this thought, I turn to the example of Zeus.

One of the phrases used to describe Zeus in the Iliad is “all-devising” or “god of strategy,” a testament to his nous; a slippery term we first encounter in the Iliad and whose meaning evolved over time but relates to “wit” (in the sense of outwitting others), to the ability to devise or strategize, and to understand and perceive things properly. Zeus’ nous is held to be superior to other’s, both mortals and gods.2 Nor does the mightiest of the Olympians feel the need to share his thoughts and designs, as he makes clear to Hera, telling her he will reveal his thinking only when he is good and ready, and then only as much as he desires. In this way, we are told Zeus is supposedly not only stronger than the other gods, but superior in intellect and understanding.

What are the implications here, for the story of the Trojan War as a whole, of which the Iliad is the key part? To explore this, I would like to engage in a thought experiment: follow the notion of an “all-devising” Zeus – or “god of strategy,” if you prefer – to its logical conclusion and see where we end up. Although they are familiar, I will for completeness review the basics of the situation, following the more common traditions for brevity’s sake.

It all began when Gaia complained to Zeus she was overburdened with humanity. Zeus consulted with Themis,3 a consort of his, who personified divine order and proper custom.4Together they decided a devastating war was the answer. Then a wrinkle appeared: Zeus was enamored of Thetis, queen of the Nereids, but Themis revealed that if she and Zeus had a child, he would be greater than his father. Zeus, having deposed his father Cronos, who had in his time deposed his father, Ouranos, was sensitive on this issue. Accordingly, it was decided to marry Thetis to a mortal.5

The mortal selected was Peleus, hero-king of Phthia, but (as always) there’s a catch. Thetis isn’t thrilled with the idea, and demands Peleus defeat her in a wrestling match.6 This is a high bar to clear, because Thetis changes shape repeatedly while they wrestle,7 and Peleus only wins with divine assistance. In other words, he cheats.8

Ignoring the maxim “Cheaters never prosper,”9 the gods held a sumptuous feast to celebrate the wedding at the abode of Chiron, the wise centaur, who will play a major role in their son’s upbringing. But Zeus barred Eris, the goddess of discord, because she always made trouble. Eris, predictably annoyed, showed up anyway and when denied entry tossed a golden apple into the feast as a “prize” for the “fairest.” This is the famous Apple of Discord. Hera, queen of the gods; Aphrodite, goddess of love and sex, and Athena, goddess of war and wisdom, all claimed it. Unable to resolve the issue, they appealed to Zeus and Zeus, not being entirely stupid, would have nothing to do with the question.

Eventually, they found a judge: Paris, a Trojan Prince who’s living happily as a shepherd, unaware of his royal birth. It had been foretold that he would cause the fall of Troy, so his father, King Priam, had him exposed, but he was either rescued by shepherds or handed over to them by Priam and/or Hecuba, his queen, who were loathe to kill him.

So there’s Paris, innocently tending his flocks on Mt. Ida – a place Aphrodite knew well as she conceived the Trojan hero Aeneas there with her mortal lover Anchises – when three goddesses appear and ask him to decide who is the most beautiful.

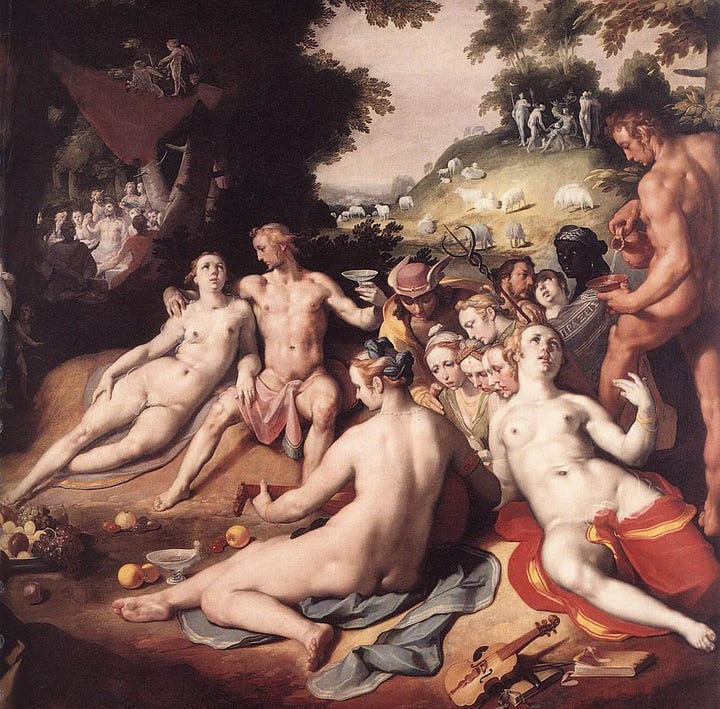

Paris has trouble making up his mind. Each of the three offer him a bribe. Details vary but according to Proclus, Hera offers “kingship over all,”10 Athena offers victory in war and Aphrodite (keeping it simple) offers sex. When Paris still balks, a scene of epic titillation results: the goddesses strip (much to the delight of painters and their patrons ever since).11 That decides it and Paris, in typical male fashion, opts for sex. Unlike Anchises, however, Aphrodite isn’t offering sex with her, but Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, despite the fact she is already married to Menelaus, king of Sparta and brother of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae. Nevertheless, Paris is (shall we say) down with it.

With the goddess’s assistance, Paris either abducts or elopes with Helen, supplying the casus belli for the Trojan War. As a bonus, Achilles, the son of Peleus and Thetis, is destined to die in this war, forever removing the threat to cosmic order that he posed; apparently marrying Thetis to a mortal was not good enough and Zeus and (we may assume) Themis were taking no chances.12

The war ensues, Achilles dies, Troy falls and with it, the “Age of Heroes” comes to an end.13 The designs of Zeus have been realized. What are the implications of this that I referred to at the outset?

Let me start with Eris. It seems Zeus must have “banned” her from the wedding for a reason other than she causes trouble. Unless she was in the habit of keeping apples of discord on her person, she must have been prepared for being refused at the door and brought one along. This suggests she was acting on the orders of Zeus.

That raises another interesting point: the three goddesses who claim the apple are Hera, Aphrodite and Athena. Why those three? Aphrodite is the goddess of love and sex, so she appears to be a natural one to claim to be the fairest, Hera is queen of the Olympians and would probably like to have precedence, but Athena? Why would the goddess of war and wisdom get involved? It doesn’t sound much like her. Artemis, the goddess of the hunt and wild things, might seem more likely, but either she had the good sense not to get involved or disqualified herself because she didn’t like the idea of being in a divine beauty contest. After all, she asked Zeus to grant her perpetual freedom from men so she could dwell forever “untamed on solitary mountains.” Zeus complied and thereafter the gods gave Artemis the name “Virgin Deershooter Wild One” (according to Sappho, who understood these things).14 She also had a temper (as Acteon would attest to, if he could still talk) so perhaps her abstention was just as well.

But may I propose that Zeus is trying to start a war, so involving the war goddess makes sense? Further, Athena is the daughter of Mêtis and mêtis (“magical cunning”) is one of her main attributes (unlike Ares, who’s basically a thug given to brute force);15 a crafty plan to start a war is right up her alley, as it were. Nor should we discount Aphrodite. Zeus needs Paris and Helen to get together and run off with each other; what better agent than the goddess of desire to facilitate this? Aphrodite, as we know, has irresistible power over gods as well as mortals. She is the one deity who can certainly make this happen.

What about Hera? Is she in on the plot? It seems unlikely. She and Zeus are generally at daggers drawn and he is brusque in telling her to mind her own business. As his plan is ultimately to destroy Troy – which she loathes – if she knew the truth, there would be no reason for her to connive as she does. Zeus seems to be keeping her in the dark, perhaps out of spite and/or simply because he does not trust her.

So like the wrestling match, the Judgement of Paris was rigged from the get-go. Zeus intended Aphrodite to win, Athena knew it and was brought in to help Zeus’ plan along and provide cover for the rigged contest. She and Aphrodite were actually working together when they appear to be at odds. They’re both powerful cunning women who know how to maneuver things to their advantage, or Zeus’ advantage in this case.

That brings us to Apollo. What did he know and when did he know it? He sang and played his lyre at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, appearing to promise great things for their son and has been condemned for his duplicity (indirectly in the Iliad and explicitly by Aeschylus) because it is he who will cause Achilles’ death. Was he acting in good faith at the wedding, only to be ordered to play his part in the scheme later? That is a good question. Given his association with prophecy, it seems likely he would be aware of Achilles’ fate. So we can have some confidence he was playing a role at the wedding, just like Aphrodite, Athena and Eris.

We might also note that while Apollo is a supporter of the Trojans, he is also in Zeus’ doghouse for the transgression that led to him and Poseidon being sentenced to build the walls of Troy as mortals. In contrast to Poseidon, who is Zeus’s brother, Apollo is not in a strong position to defy his father and is arguably better placed than his uncle to aid Zeus in his scheme – specifically to bring about the death of Achilles at the Scaean gates, as he (the archer god) plays a direct role here.

This may further illuminate another curious aspect of the Iliad: the treatment of Hector by the gods. Throughout the epic, Hector believes he has the gods’ favor; he is described as “beloved of Zeus,” sends prayers to Athena (who has a temple in Troy) and believes Apollo to be on his side. He disregards sensible advice (inspired by a bird omen) on the grounds he received a sign from Zeus that trumps said omen. When the final confrontation with Achilles happens, Apollo and Athena connive to bring about his doom; Athena goes so far as conning him into standing his ground and then betrays him. The reason is both gods are acting on orders from Zeus; Hector must die to ensure Achilles’ death according to prophecy.16

In this way, Hector becomes a divine sacrifice, and an otherwise disreputable and duplicitous act is portrayed as necessary in the name of preserving cosmic order. The way is cleared to bring about Achilles’ fate, which Apollo does at the next opportunity. All that remains is for Troy to fall to accomplish the designs of Zeus (and Themis) and we (supposedly) are assured this will happen in due course.

Now let us turn our attention to Thetis, the central figure of this tragedy. In Aesculus, the suggestion is made that she is unaware of her son’s fate when she angrily accosts Apollo for misleading everyone at her wedding when he knew he was destined to kill him (as we do not have all of this particular play, we don’t know how the situation is finally resolved, if it is). This passage has been described as problematic.17 But since in the Iliad, Thetis is clearly aware of her son’s fate and frequently reflects on it, the simple explanation is that Aesculus is exercising artistic license to heighten the dramatic effect in his play, not relating an alternate tradition of which he was aware.

It is hard not to feel great sympathy for Thetis: first, she is subjected to the unwanted attentions of Zeus (and maybe Poseidon), putting her in a crossfire between Zeus and Hera. Then she is forced to marry a mortal, initially against her will, and finally, her son is to be killed – one might say, judicially murdered – when she has been the agent for protecting Zeus and other gods as well. This is a lot for anyone, especially a deity, to suffer and it puts a different light on her interceding with Zeus on Achilles’ behalf, as well as Zeus acceding to her request despite the problems it will cause with Hera. Zeus not only owes her for a past favor, but for planning to kill her son and while Thetis knows she cannot reverse his decision, she can ask Zeus to ensure that he is glorified in eternity and not subjected to Agamemnon’s slights.18 Her translating Achilles to the White Island (or any of the other places mentioned in the various traditions) might be seen as a further quid pro quo for enduring his fate.19

Finally, we come to the last, and in many ways most crucial person in this epic, Helen, and things take a decidedly unpleasant turn. Helen is the instrument on which Zeus’ whole plan hinges and to call her simply the most beautiful woman in the world is to sell her short. Helen must be more than just beautiful – she must be so powerfully captivating, alluring, enchanting, that men will destroy their entire world for her. One of Homer’s most powerful moments in the Iliad is when Helen appears on the ramparts of Troy. Rather than attempt to describe her, he describes the reaction of the Trojan elders, a rather desiccated set of men he likens to cicadas, when they see her. Despite the mortal peril she represents to them and their city, despite their wish she would just leave, they all freely admit that this is a woman worth going to war over and dying for.

We may doubt a mortal woman could inspire this, but Helen is not mortal. Prior to Euripides making her the daughter of Leda (the myth most widely known) the Cypria made her the daughter of Nemesis, who was pursued and assaulted by Zeus.20 Thus Helen is a full-fledged goddess in this tradition, and not only that but one of exalted pedigree, taking precedence over any Olympian. Nemesis is said by Hesiod to be the daughter of Night without the benefit of a male partner.21 Night is a primordial deity – in some traditions, the primordial deity – and (according to the Iliad), one Zeus must defer to and indeed may fear. Her daughter is therefore older than Zeus himself.

Further, Nemesis is the goddess who delivers and carries out the judgements of Themis, especially on those who commit hubris – a powerful responsibility. In forcing himself on her, it would seem Zeus was playing with fire, risking the wrath of two goddesses that are superior to him. What, I might ask, is going on here?

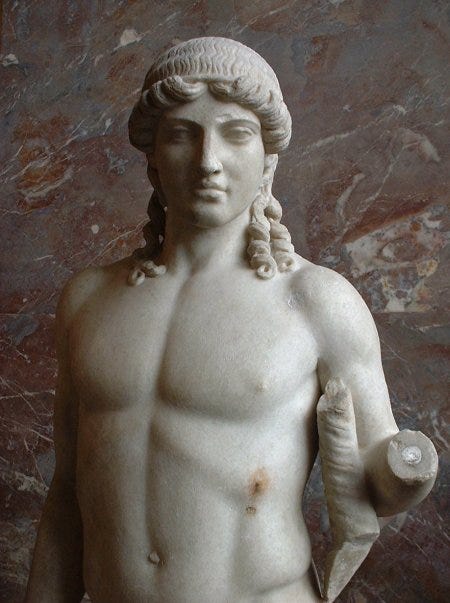

Observe that (parentage according to Greek myth aside) Helen is a deity of most ancient lineage: the proto-Indo-European Sun Maiden, or Daughter of the Sun, who according to broad Indo-European tradition emerged from an egg.22 A comparison to Aphrodite is instructive: according to Hesiod, Aphrodite was born when Ouranos’ severed genitalia fell into the sea, making her a primordial goddess of a sort, but in the Iliad, she is the daughter of Zeus and Dione, a deity to whom various origins are ascribed. Thus, Helen would seem to be on a par with Aphrodite in mythic cosmology and older in historical chronology.

Yet, as I point out in my essay The Three Faces of Helen, she is portrayed as mortal in the Iliad with no hint of a divine nature except in one scene where she confronts Aphrodite and talks back to her in terms no mortal would likely use to an Olympian: Book 3 of the Iliad, where Helen tells Aphrodite that if she is so enamored of Paris, she should forsake Olympus and take up with him until he makes her either his wife or his slave girl. A mortal suggesting a goddess should be enslaved by a mortal is not the kind of thing we’d expect and the exchange, including Aphrodite’s tart rejoinder, sounds more like a spat between two goddesses who know each other pretty well.

Helen’s dual character is a topic I address in my Helen essay, but suffice to say that she has a divine attraction equal to Aphrodite herself and Dawn (Eos), the goddess that she (as the Sun Maiden) has the most in common with.23

Returning to my thought experiment, Zeus needed Helen so he had to create her and no mortal mate would do. Therefore, he impregnated Nemesis as part of his plan, long enough before the marriage of Thetis and Peleus for her to mature so Aphrodite can offer her to Paris.24

Readers will have gathered by this point that things have gotten ugly. Nemesis, we are told, did everything she could to resist Zeus’ advances, changing shape again and again, but was eventually overpowered.25

So what was Themis thinking? Did she set up her right-hand woman to get assaulted by Zeus, in order to conceive Helen and carry out their plan? Is this how far she will go in the name of preserving Cosmic order? The list of casualties is growing: Achilles, Hector, Thetis – besides all those killed or ruined in the war to unburden Gaia, and those like Iphigenia and Polyxena who just seem to be collateral damage – and now a senior goddess?26 Did she give Nemesis a choice? If not, why not?

If so, why did Nemesis go along with it, then act the way she did? Is something else we have not yet fathomed at work?27 At best, this seems like dubcon at its most dub. However we look at it, it appears to be a very twisted plot, from beginning to end; something only Zeus, with his supreme nous, is capable of devising, right? So here we have literary evidence of, and justification for, what the Trojan War narrative and its narrators say about “all-devising” Zeus.

Or do we? Yes, it is all quite twisted and that is the point. By that I mean, my whole thought experiment, which has now come to an end, is an exercise in twisty logic.

There is no reason to believe that anything I have proposed reflects what was on anyone's mind during the centuries over which the Trojan War legend was being conceived and assembled, in whole or in part. Bits and pieces may have been, now and then, here and there, but nothing like the entirety of it.

What exactly have I done here? I’ve selected some of those “bits and pieces” of the legend – you could say, cherrypicked – from a vast array of sources, arranged them in the accepted order (more or less), then cooked up relationships between them to weave a knotted skein about the nous of Zeus. It all has a rather Goldbergian feel to it.28

Stepping back and taking a big-picture look at the whole thing, it’s about as plausible as dissecting Jane Austin to see if she might have been aware of Pride and Prejudice with Zombies29 and how it may have influenced her writing.

Yet, in Homeric scholarship, things appear that don’t look much different from that same big-picture perspective, though without the snark. Pieces are shifted around, in both time and priority, slotted together, scrutinized and anatomized and turned inside out, then woven into a hypothesis, the big picture getting lost somewhere along the way.30

Despite my tone in this essay, I do not mean to disparage the work that has been done and is being done. It is valuable, necessary and worthy of respect. Therefore, with full appreciation for these efforts, I shall end this essay as it began: when confronted with vague, contradictory and incomplete data, we naturally strive to make sense of it, to find coherence, to create a satisfying narrative. This (repeating myself) is our job. But it goes deeper than that: we are storytelling creatures, creating stories is at the heart of our psychological make-up, we literally can’t help it. But if we’re not careful – and by careful, I mean keeping a weather eye on the big picture as well as all the enticing details – we can get out over our skis.31 Narratives suck us in and none of us are immune to their allure. As Eric Luttrell impressed me by saying, good narratives make for poor explanations. Those are words for scholars to live by.

Postscript

As readers might guess, Helen has been on my mind, so as I wrote this, a subsidiary question imposed itself upon me: What agency did Helen have in all this (the Trojan War, however conceived)? Was she aware of the role she was destined to play? In the Iliad (quoting Martin West) she “recognizes the will of Zeus, she is sorrowful but not embittered, resigned but not complacent.” She “behaves perfectly in every situation” and she comes across as the “most marvelous, sincere, sweet-natured woman in ancient literature” – sentiments with which I heartily agree.32 This might lead us to suspect she does know and accepts, as far as is possible, her role in a cosmic tragedy.

Priam, who seems to have a good bead on things, says as much: no blame for the war should attach to her. Hector was always her friend, unfailingly kind to her and defending her when others would not. Like Achilles, like Hector, like Thetis and all the other many casualties, Helen is a kind of sacrifice on the alter of cosmic order – or so we might believe. Afterwards though, we see her in Sparta through the lens of the Odyssey poet, reunited with Menelaus in what Gregory Nagy describes as a kind of “Mycenaean heaven,” her divinity restored.33

The “Age of Heroes” may have come to an end, but the worship of Helen continued into Homer’s day and well beyond. Even now, more than two and a half millennia later, she is still with us, her allure and her fame undiminished. Truly immortal, the Sun Maiden might be said to have eclipsed all her fellow deities. Perhaps, in some measure, Zeus has paid her back.

Was that also part of the plan?

Footnotes

One gained sufficient notoriety to appear in a Tom Clancy novel.

It did occur to me to title this paper “The Nous of Zeus,” but as that sounded a bit like something that might have been by Dr. Seuss, I decided to refrain.

In another tradition, Momos confers with Zeus, but I will stick with Themis for this discussion.

She first appears as the personification of justice in Hesiod’s Theogony where she and Zeus are the parents of Dike (goddess of justice in the human realm.)

In the Cypria, Thetis successfully rebuffs Zeus in order to stay on Hera’s good side and Zeus, in a huff, declares if he cannot have her, no god would, and decreed she be married to Peleus. Pindar adds the detail that Zeus and Poseidon were in competition for Thetis’ favors, providing another motivation to marry her to a mortal.

Such a match has its origins in ancient Indo-European myth.

The protean nature of water spirits is also of the ancient lineage; see Proteus himself, who changes shape when anyone attempts to capture him.

It is notable in this regard that Peleus earlier lost a wrestling match to Atalanta, the Greek “Amazon.”

Arguably he didn’t prosper in the end.

The nature of Hera’s bribe depends on the source. Some say she offered a “good marriage” (a profitable one). Hera was originally a goddess of sovereignty, a common feature of Indo-European belief systems and in her Roman counterpart, Juno, her role as a goddess of sovereignty (protector of state power) is present along with her role as the protector of marriage. Kingship seems like a better bribe than a “good marriage” and more in keeping with Hera’s role as a protector of state power. Offering a “good marriage” appears to emphasize Hera’s domestic aspect as the protector of marriage at the expense of her being a goddess of sovereignty. See Robert Fagles’ and Emily Wilson’s translations of the Iliad for more discussion of these variants.

This is likely a late addition to the myth. The ancient Greeks believed no mortal could survive beholding a naked deity, which is why Praxiteles (4th century BC) caused such a sensation with his sculpture of Aphrodite, the first realistic, life-sized female nude in history.

The behavior of Themis here is interesting on two counts. First, later authors postulated that Earth’s denizens in the former age were iniquitous in some degree, explaining her willingness to eliminate them. Second, according to Hesiod's Theogony, Themis is one of the twelve children of Gaia and Ouranos. As such, she seems to have posed no objection to her brother Cronos overthrowing their father, or to Zeus deposing Cronos. Both Cronos and Ouranos are depicted as causing distress to their consorts, so Themis sided with her mother and sister, but here she sides with her consort in deciding the possibility of Zeus being overthrown is a threat to cosmic order. This all has rather the air of ex post facto justification to it, and might also relate to the political situation at the time this myth became widespread. I’ll take up that point later.

This is the Bronze Age Collapse.

I think this is about the coolest goddess name ever!

In ancient Greece, Ares seems not to have enjoyed the preeminence he would ascend to in Roman society, as Mars. In the Iliad, Diomedes stabs him and runs him off the battlefield while Athena easily smacks him down in the set-to between the gods, and the Odyssey relates a story of Hephaestus making a fool out of him. Zeus even calls him the most hated of the gods. It’s hard to imagine the Romans treating Mars this way, although they did retain a version of the Hephaestus story.

Here we encounter the question of how much leeway Zeus actually has. He simply cannot smite Achilles with a thunderbolt it seems; he must let the prophecy do the work. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Hera implies Zeus is not always bound by what his golden scales reveal, but there are consequences if he disregards them.

See Ioanna L. Hadjicosti: “Apollo at the Wedding of Thetis and Peleus: Four Problematic Cases.” L’Antiquité Classique, vol. 75, 2006, pp. 15–22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41665276.

The concept is proto-Indo-European (*ḱlewos *ndhgwhitom); in Greek: kléos amphion, “glory imperishable.”

The Odyssey poet consigned Achilles to Hades, so Odysseus could talk to him. His reason is obscure as it would seem to have been simple, given the scope of Odysseus’ wanderings, to have him land at the White Island and meet Achilles’ ghost in his shrine there. Perhaps the poet wasn’t aware of the White Island episode, or did not find it suited his purpose or he simply didn’t want to add another scene to his already long epic.

Hesiod does mention that Leda was Helen’s mother, but this need not imply she was Helen’s birth mother, only that she raised Helen as her daughter. It seems more likely the traditions of the time held that Helen was fully divine.

Other traditions make Nemesis the child of Night and Darkness (Erebus).

See Martin West’s lecture, Immortal Helen, 1975, for a concise and illuminating discussion of Helen as the Sun Maiden.

Helen was apparently worshipped as a dawn goddess in Sparta. See Gregory Nagy, “Just to look at all the shining bronze here, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven”, February 18, 2016. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/just-to-look-at-all-the-shining-bronze-here-i-thought-id-died-and-gone-to-heaven-seeing-bronze-in-the-ancient-greek-world/.

I recall it being argued that Aphrodite promised Helen to Paris before she was conceived, making him wait years for the promise to be fulfilled, but this not only seems like more ex post facto justification, and it’s counter to Zeus’ superior nous.

West asserts that this may have been carried over from the myth of Thetis, which is a reasonable supposition, but both myths could also have a common “mythic ancestor.”

Sadly, the saying “you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs” is taking on a whole new meaning here. Regarding Iphigenia and Polyxena, the former originally seems to have been spared (replaced with a deer by Artemis) or becomes a goddess (according to Hesiod) and the latter, by one account, becomes Achilles’ bride in the afterlife. So there were some attempts to put silver linings on all the most unfortunate incidents.

A scary thought…

I’m not sure how familiar people still are with Rube Goldberg; he was popular in the days of my youth. We got models of his contraptions, and they were great fun to assemble and frustratingly fun to make work. (Thus illustrating his point. I particularly remember this spoked wheel with a boot on the rim; its purpose was to roll down an incline and kick a marble into a chute. All the engineering factors involved were fascinating: the mass and diameter of the wheel, the angle and length of the incline to develop the proper impetus, whether the incline should be curved or straight, the mass of the marble and the specific impulse necessary to dislodge it from its perch without knocking it too far; are all important factors, the calculation of which would be mindboggling if attempted via classical mechanics, which I got a C in.) With that in mind, I probably should dedicate this essay to Rube Goldberg, along with James Burke whose show Connections (late 1970s) investigated interconnections in the development of science and technology with much enthusiasm but not always matching rigor, and especially to Wile E Coyote, whose manifold expressions of the Law of Unintended Consequences are the most eloquent ever produced (IMHO) and made a profound impression on my young and developing mind (they were also the only thing that would entice me out of bed early on a Saturday morning). Those (as was once said) were the days.

I think there might be a work of that title? I forbore to check.

A particular example that niggles me is the once popular (and maybe still popular?) idea Homer was inspired by the end of the Aethiopis – Memnon and all that – not the other way round. I’m in league with Martin West on this and will have more to say about it in the future.

I once found an article – by an actual Classical scholar – making similar points after I formulated this argument several years ago. Try as I might, I can’t recover it. When I do, I will update this essay in deference to his more learned views.

It is ironic that this first appearance of Helen in literature is perhaps also the most sympathetic. As West says, Homer is “clearly enthralled with her” and his genius has led to us being captivated by her ever since, whether positively or negatively.

See Gregory Nagy: “Just to look at all the shining bronze here, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven: Seeing bronze in the ancient Greek world”, February 18, 2016. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/just-to-look-at-all-the-shining-bronze-here-i-thought-id-died-and-gone-to-heaven-seeing-bronze-in-the-ancient-greek-world/.

Indeed, Sappho did know those things! That comment made me laugh. Thanks for another great read!